Hi there! It’s Amy Sun and Daniel Kim again, two seniors at the University of Washington Informatics program with a focus on UX/UI design. We’re currently working on a capstone project with the Flickr Foundation on digital preservation, digital legacy, and the many nuances and considerations that come alongside those.

This is the 2nd of our blog posts about our Capstone project (you can find the first one here). In this post, we dive into the user research and concept development phase of our project.

Interviewing, Analyzing, and Developing

In the next phase of our project, we conducted stakeholder and user interviews, developing user personas and user journeys based on the information we collected. This was an important step in our design process because it allowed us to lean into the experiences and viewpoints of real people working in the realm of archives or users in a digital environment.

We conducted two stakeholder interviews with experts in the field of digital collecting:

- Andrea Lipps, Curator of Contemporary Design and Head of Digital Collecting Department at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum

- A PhD student at the University of Washington iSchool focusing on Indigenous archival practices, who requested to remain anonymous in our research

Following this, we ran nine user interviews with our classmates and peers, asking about their experience with photography, online archiving, and social media.

Here are the insights we gathered from these interviews that have shaped our thinking:

- Ongoing consent: we learned about institution’s need to ask for consent continuously, no matter how many times a ‘yes’ has been given, one must always ask for consent with digital materials.

- Collecting vs archiving: we pieced apart the difference between collecting (gathering for a central theme for display), and archiving (gathering for the purpose of preservation).

- Digital surrogacy: we encountered the concept of a digital surrogate, something that provides evidence of existence of an object or artifact – a picture, video, or any media relating to the original artifact.

- Autonomy: we reflected on the skepticism of Indigenous peoples to preserve information online for fear (and past experience) of it being used negatively or inappropriately.

- Ownership: we thought deeply about the ethics of ownership of family photos taken by or stored by institutions, in the context of Indigenous histories.

- Literacy: specifically from our interviews, we got thinking about the literacy of Gen Z students around the concept of digital legacy and preservation. Our interviewees expressed a lot of practices they used in terms of photography and social media that were very similar to preservation practices, but they did not have the right terminology to describe it.

While laboring with these newfound concepts of how people view archiving in both the professional and “amateur” realm, we began to explore design opportunities. We explored embedding ongoing consent models–inspired by frameworks like the C.A.R.E. principles–reimagining how Data Lifeboats can be “living” documents where consent can be revised at any point of its lifetime. We also explored the possibility to change the display and packaging of Data Lifeboats to allow for “positive friction”during archival workflows that prompted reflection and created a meditative experience when creating a Data Lifeboat. While looking at what ownership and autonomy of a Data Lifeboat look like when a body like the Flickr Foundation gains stewardship over digital artifacts, we recognized a disconnect: these solutions presupposed a baseline engagement with digital preservation that most users lack.

The Data Lifeboat concept, though vital in the Flickr Foundation’s mission, assumes creators already value long-term stewardship – a perspective shaped by the Flickr Foundation’s unique position as a cultural repository. In reality, mainstream users rarely consider archiving and legacy planning without explicit prompting. Why would someone painstakingly curate a lifeboat if they don’t grasp the fragility of digital memory or the stake we have in preserving our histories. We believe if the Foundation wants to democratize the curatorial power to common users, they need to diffuse their values downstream.

This realization reframed our capstone focus: instead of iterating on the Data Lifeboat itself, we pivoted to building literacy that makes preservation’s value tangible – linking archival theory and public motivation. If we can cultivate understanding necessary for lifeboats beyond the niche community of archivists, collectors, and institutions, then memory work can truly be shared among everyday people. Decentralization, democratization, or whatever word best fits this shift in archival work, creates a resilient and distributed network of care that is sustained collectively.

Our user interviews revealed that Gen Z engages in informal archival practices through daily social media behaviors–liking, saving, curating “photo dumps” and posting–yet lack the awareness of how these actions are actually translatable to archival work. Despite being digital natives, the first generation to inherit a fully digitized world, the way they view preservation is reactive (e.g. saving viral posts or curating photos) rather than strategic to long-term cultural preservation. So why Gen Z? We believe that Gen Z is at an inflection point, ripened just enough to shift their “micro-archives” like individual photo dumps or saved collections into intuitive archiving behavior.

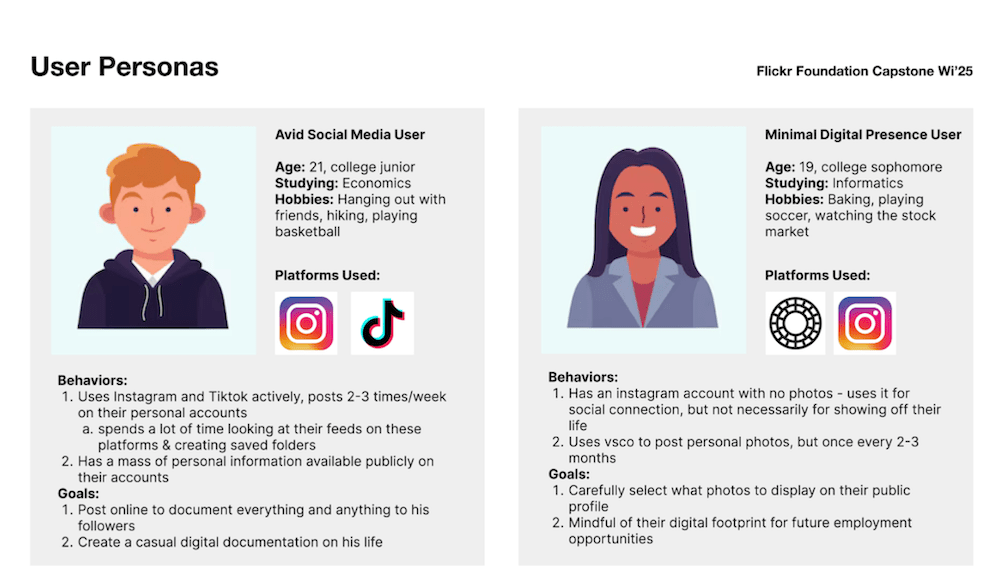

To understand this demographic, we developed two user personas to help us better understand the gaps, needs, and goals.

These two user personas were created with the intention of representing two ends of the spectrum within unconscious archiving on social media. On one end, we created the “Avid Social Media User” who lacks intention when posting on social media highlighting a disconnect between digital documentation and digital legacy planning. On the other end, we created the “Minimal Digital Presence User” who is intentional about their social media presence and cares more about photo sharing as a personal repository. Both sides of these personas highlight that anyone can be practicing archival work unbeknownst to themselves.

With all of this information, we concluded that the best way to reach and interact with Gen Z students was to hold an in-person workshop, discussing the use and impacts of digital preservation for this generation. We want to empower youth to think about their digital legacies, through educating them on the importance of digital preservation, and through translating everyday social media interactions into archival practices.

You can read more about how this workshop went in the next blog-post!