From Desiderata to READMEs: The case for a C.A.R.E.-full Data Lifeboat Pt. II

by Fattori McKennaThis is the second installment of a two-part blog post where we detail our thinking around ethics and the Data Lifeboat README function. In this post, we’ll discuss the outcomes of the exercise set during our Mellon co-design workshops, where we asked participants to help design the README prompts with C.A.R.E./F.A.I.R. in mind.

As detailed in our previous blog post, a README is a file type commonly used in software development and distribution to inform users about the files contained in a directory. We have adapted this container for the purposes of the Data Lifeboat to add detail and description beyond what is local to the files on the Flickr.com platform.

A README for Anti-Accumulation and Conscious Selection Practices

The inclusion of a README encourages Data Lifeboat creators to slow down and practice conscious description. We are resolute that the Data Lifeboat shouldn’t become another bulk download tool—a means of large-scale data transfer from Flickr.com to other platforms or data banks (which would risk the images potentially becoming detached from their original content or sharing settings). Instead, we have the opportunity with the README to add detail, nuance, and context by writing about the collection as a whole or the images it contains. This is particularly important for digital cultural heritage datasets, as it is frequently an issue that images arrive in archival collections without context or may be digitised and uploaded without adequate metadata (either due to a lack of information or a lack of staff resources).

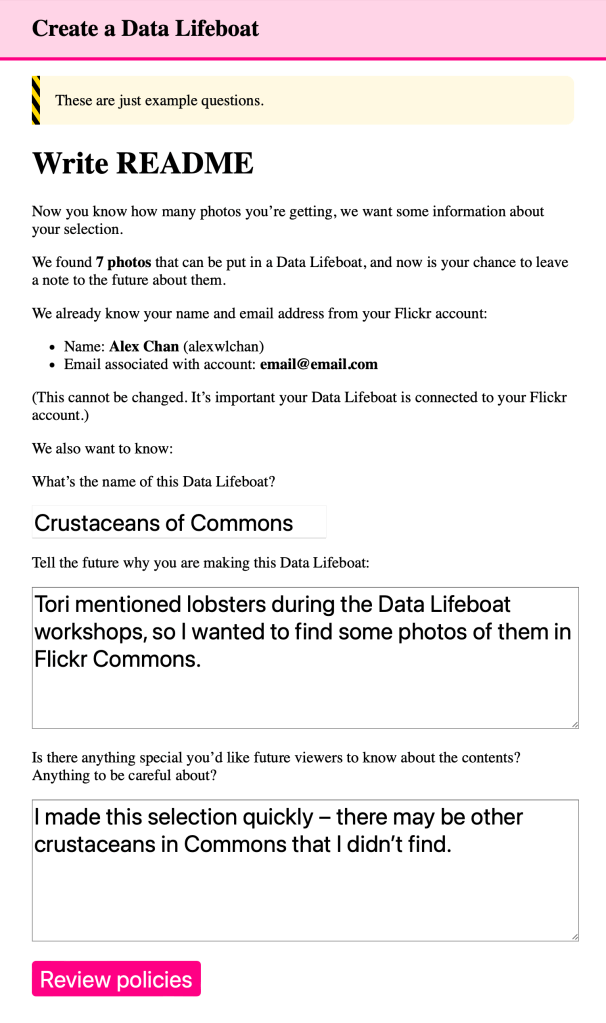

In the current prototype, the prompts for the README are as follows:

- Tell the future why you are making this Data Lifeboat.

- Is there anything special you’d like future viewers to know about the contents? Anything to be careful about?

These questions are a good start for getting Data Lifeboat creators to think about the intentions and future reception of the contents or collection. We may wish, however, to add further structuring to these questions to craft a sort of creation flow.

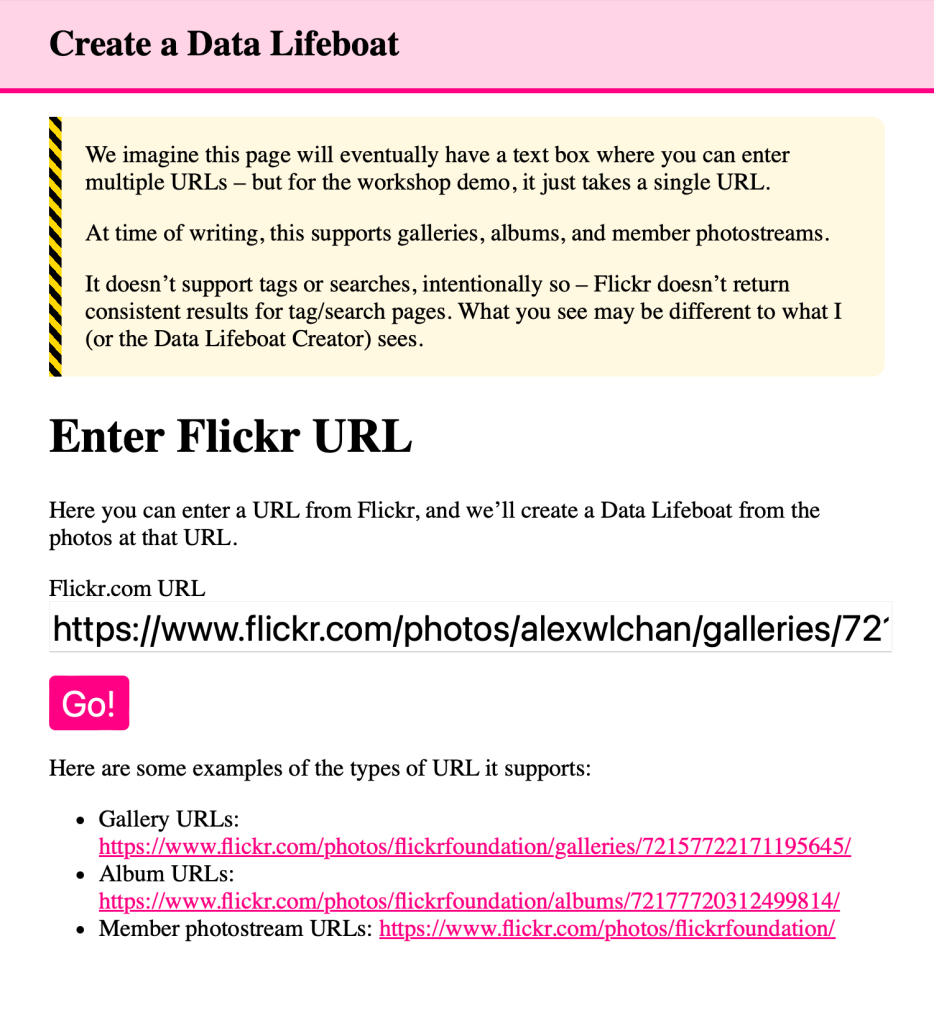

You can read more about the current working prototype in Alex’s recent blog-post.

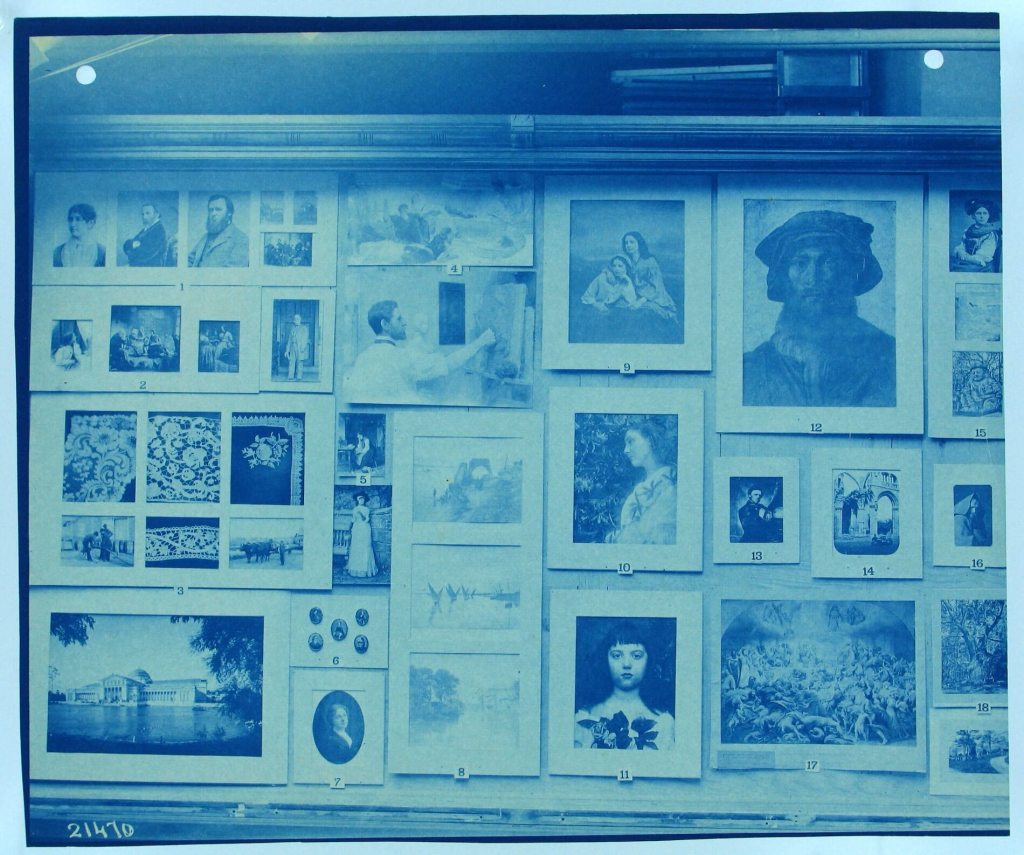

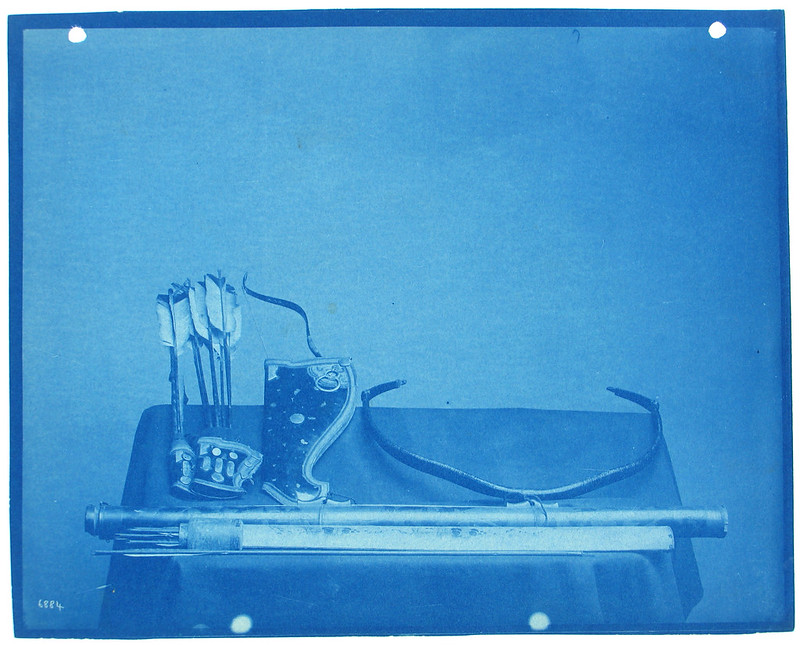

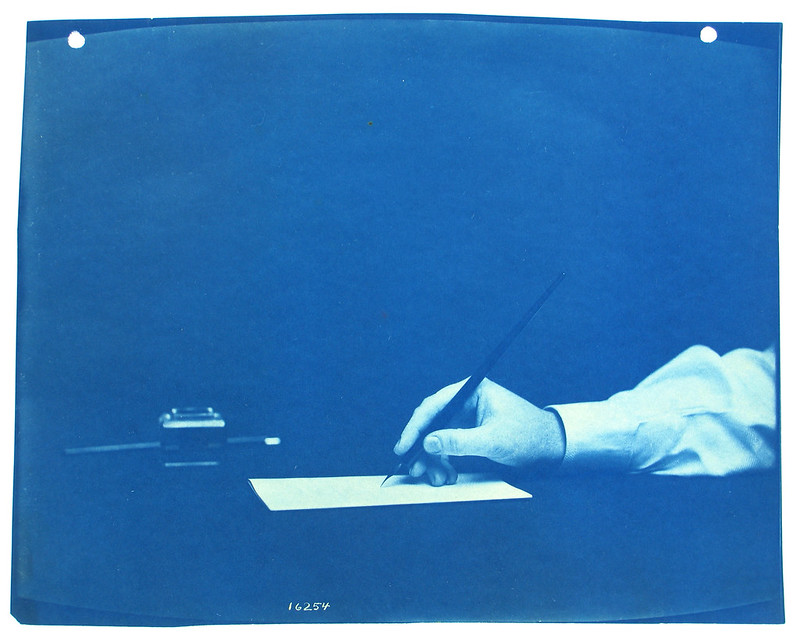

Screenshots from the working prototype:

Learning from pre-existing G.L.A.M. frameworks

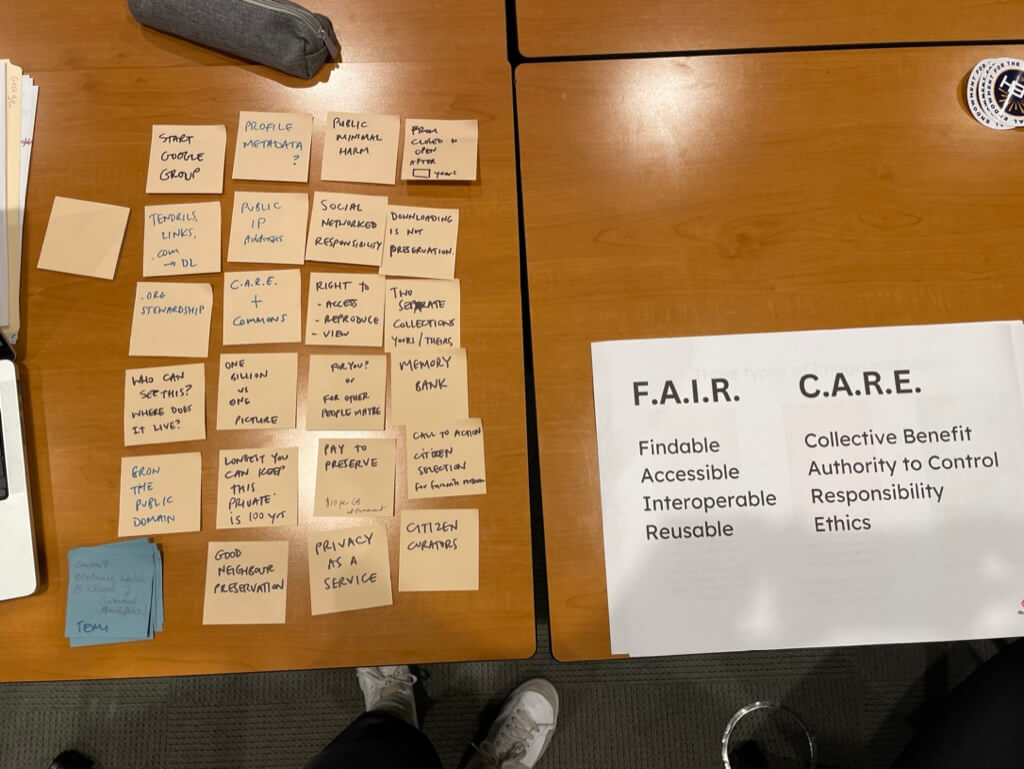

During our Mellon workshops, we asked our participants to support the co-design of the README creation flow, with the aim of prompting Data Lifeboat creators to think along the lines of C.A.R.E. and F.A.I.R. principles (detailed in our Part 1 blog post). Many of our workshop participants were already working within G.L.A.M. (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums) institutions and had experience grappling with legal frameworks and ethical responsibilities related to their collections.

In preparation for the workshop, we asked representatives to bring copies of their organisations’ (Digital) Deposit Agreements. These are formal, legal documents that outline the terms and conditions under which an object or collection is temporarily placed in the custody of the museum by a depositor. The agreement governs the responsibilities, rights, and obligations of both the depositor and the museum during the period of the deposit. These agreements often include:

- Description of contents

- Purpose of deposit

- Duration of deposit

- Custodial requirements (e.g. care, storage, maintenance)

- Liability

- Rights & Restrictions (e.g. display, reproduction, transference)

- Dispute Resolution

Digital Deposit Agreements, for the bequeathing of digital contents (such as scanned photographs, research datasets, email records, and digital artworks), may include specifications of format, versioning, metadata, digital access, technical infrastructure, and cybersecurity.

The Data Lifeboat README flow could be modelled on some of the categories that frequently arise in Digital Deposit Agreements. However, we also felt there are unique considerations around social media collecting (the intended content of the Data Lifeboat) that we ought to design for. In particular, how might we encourage Data Lifeboat creators to consider the implications of their collection across the four user groups:

- Flickr Members

- Data Lifeboat Creators

- Safe Harbour Dock Operators

- Photo Subjects

As well as a speculative fifth user, the Future Viewer.

Co-Designing the README Flow

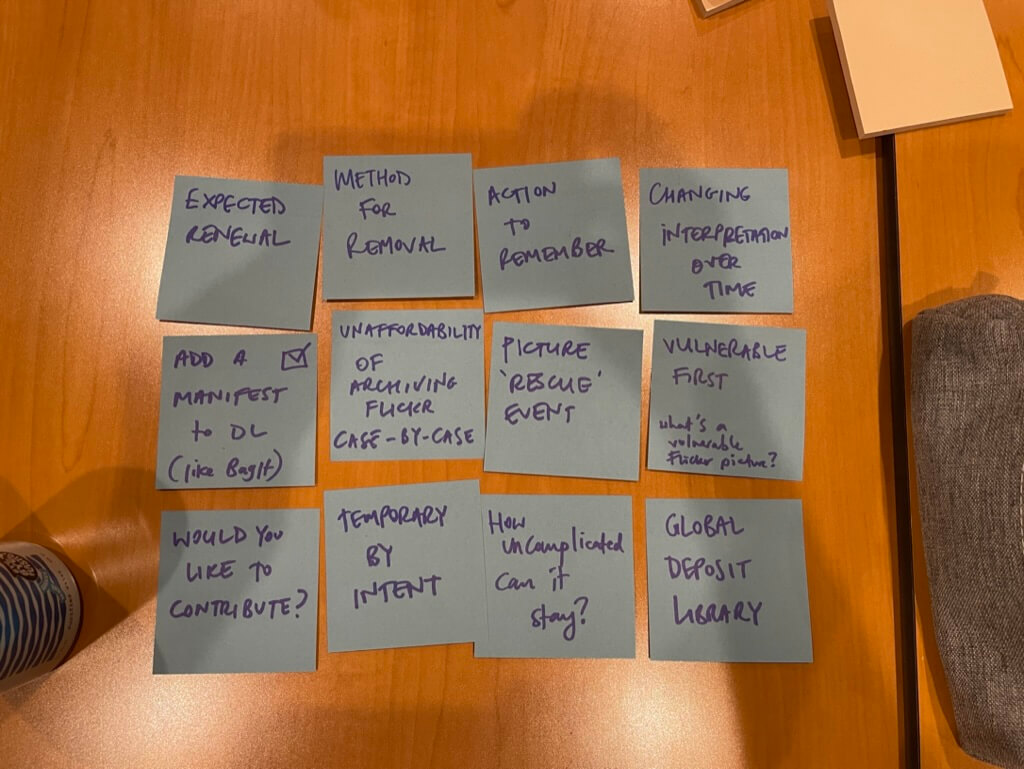

After exploring the current benefits and limitations of existing Digital Deposit Agreements, we invited our workshop participants to engage in a hands-on exercise designed to refine the README feature for the Data Lifeboat. The prompt was:

What prompts or questions for Data Lifeboat creators could we include in the README to help them think about C.A.R.E. or F.A.I.R. principles. Try to map each question to a letter.

To support the exercise, we provided printouts of the C.A.R.E. and F.A.I.R. principles as reference material, encouraging participants to ground their questions in these frameworks. Each participant created a list of potential prompts individually before we reconvened for a group discussion. This collaborative step surfaced shared concerns and recurring themes, which we have organised below, along with some sample questions as they could appear in the README creation flow.

Possible README Questions

We have broken down the README questions into 8 themes, these follow a logical and temporal flow, from present considerations to future horizons.

-

Purpose and Compilation

Why it matters: clearly defining the purpose and methods for compiling the photos in the Data Lifeboat prompts creators to reflect on their motivations and intentions.

Sample questions:

- What is the purpose of this Data Lifeboat?

- Why are you creating it?

- Why is it important that these photos are preserved?

- What procedures were used to collect the photos in this Data Lifeboat?

- Who was involved?

- Is this Data Lifeboat a part of a larger dataset?

-

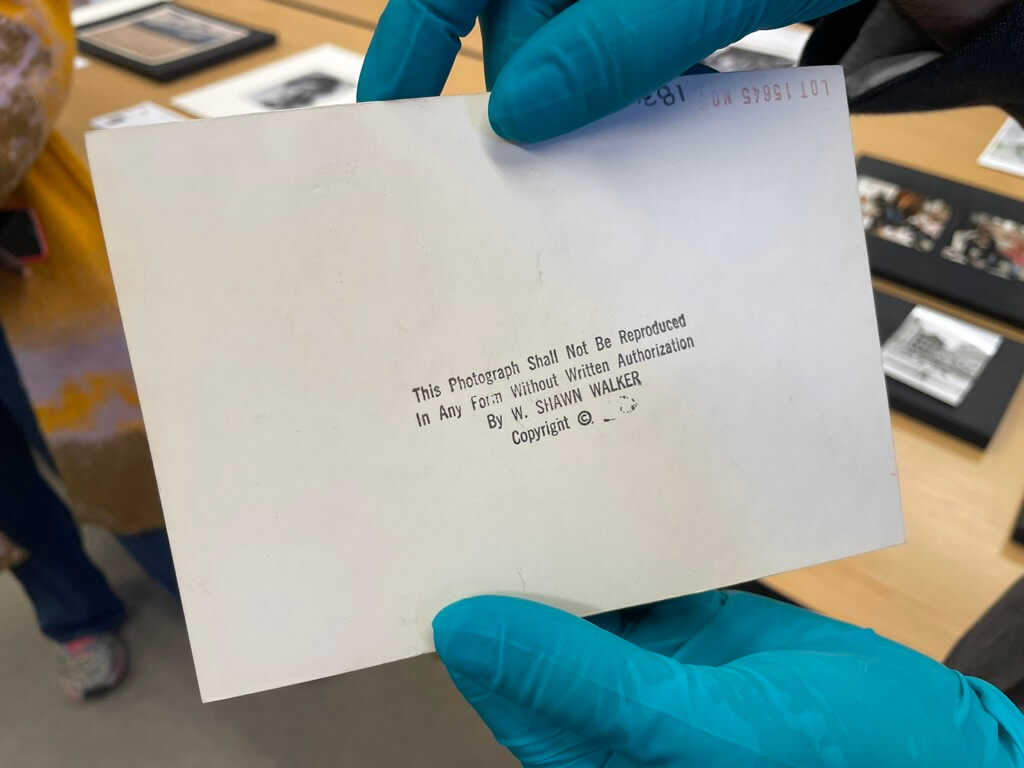

Copyright and Ownership

Why it matters: clear documentation of authorship and ownership (wherever possible) can protect creators’ rights, or attribution at a minimum.

Sample questions:

- Do you own all the rights to the images in this Data Lifeboat?

- If you did not take these photographs, has the photographer given permission for them to be included in a Data Lifeboat?

- Do you know where the photos came from before Flickr?

- Would you be willing to relinquish your rights under any specific circumstances?

-

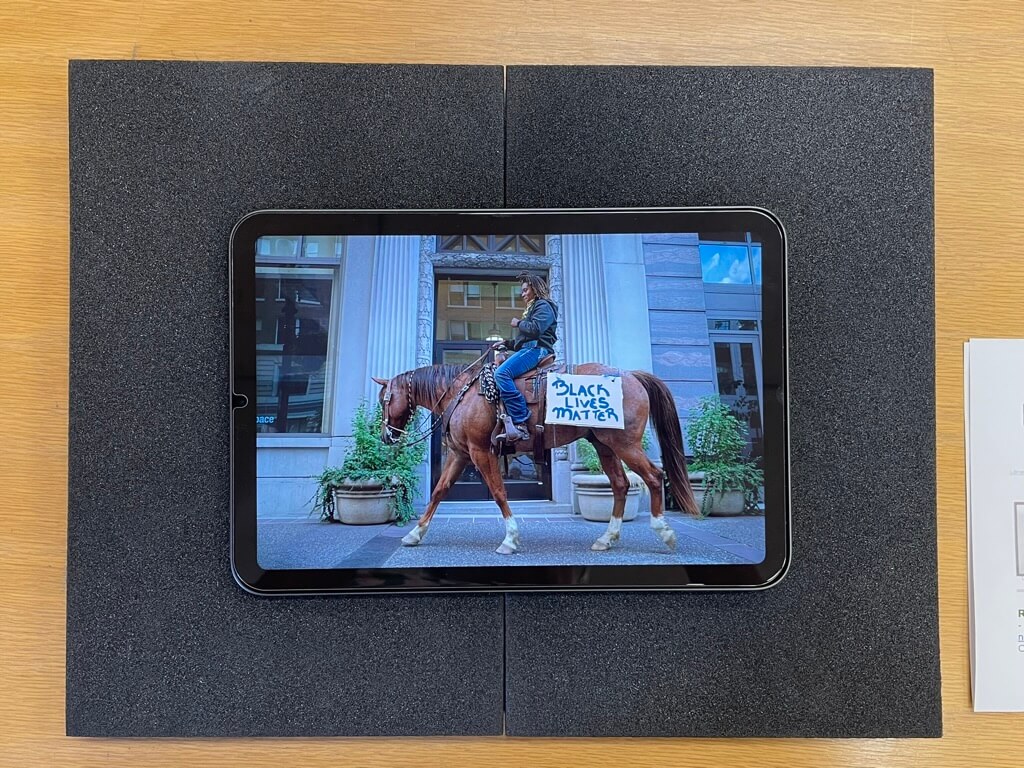

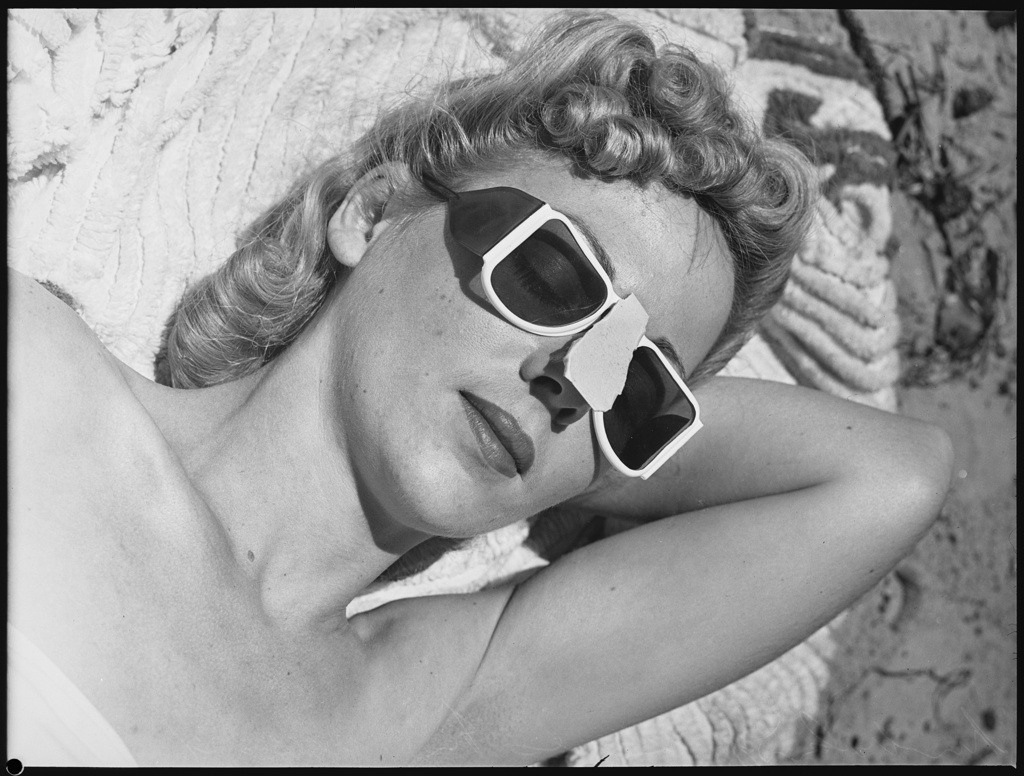

Privacy and Consent

Why it matters: respecting privacy and obtaining consent (where possible) are critical safeguards for the dignity and rights of the represented, particularly important for sensitive content or at-risk communities.

Sample questions:

- Is there any potentially personally identifiable data or sensitive information in this Data Lifeboat (either yours or someone else’s) that you wouldn’t want someone to see?

- Tell us who is in the photos, are they aware they are being included in this Data Lifeboat, could they have reasonably given consent (if not, why)?

-

Context and Description

Why it matters: providing rich, contextual information (which the free text input allows for) can help supplement existing collections with missing information, as well as helping to avoid misinterpretation or detachment from origins.

Sample questions:

- Can you add context or description to an image(s) in this Data Lifeboat?

- Could you add context to comments, tags or groups within this Data Lifeboat?

- Do the titles and descriptions accurately reflect the photos in this Data Lifeboat?

- What do you think is important about this image(s) that you want a future viewer of the Data Lifeboat to understand?

-

Ethics and Cultural Sensitivites

Why it matters: we have the opportunity to append ethics to historically unjust collections by giving space for Data Lifeboat creators to write how the images should be viewed, understood and should [more on previous interventions here]

Sample questions:

- Are you a member of the community this Data Lifeboat is depicting?

- If not, have you thought about the implications for the community?

- Are there potential sensitivities in the information stored in this Data Lifeboat that future viewers should be aware of?

- Are there historical or current harms enacted in this material within the Data Lifeboat (if so, would you like to explain these to a future viewer)?

- Think about whether this Data Lifeboat contains content that could be used in another way by bad actors, should you include them?

-

Future Access and Use

Why it matters: outlining conditions or requests for future access and use of the Data Lifeboat collection, whilst this cannot be secured, can at least serve as guardrails.

Sample questions:

- Is this Data Lifeboat just for you, or could it be public one day?

- Who will you be sharing this Data Lifeboat with? Could you nominate a ‘trusted friend’ to also keep a copy of this Data Lifeboat?

- Would you like to see the Data Lifeboat collection returned to the community (if so, who to)?

- What should or should not be done with this Data Lifeboat and its contents?

-

Storage and Safe Harbors

Why it matters: recording (or suggesting) where the Data Lifeboat could end up prompts creators to think about future viewers or stakeholders. There may be the possibility, at point of creation, to designate a Safe Harbor location and its (desired) conditions for storage.

Sample questions:

- Where will this Data Lifeboat go once downloaded?

- Who would you like to notify about the creation of this Data Lifeboat, is there anyone you’d like to send a copy to?

- Where would you ideally like this Data Lifeboat “docked”?

-

Long-term Vision

Why it matters: articulating (or attempting to) a long-term vision can help ensure the Data Lifeboat remains meaningful and intact for as long as possible, even after the creator is no longer directly involved.

Sample questions:

- Have you included enough information about this Data Lifeboat so you would remember why you made it?

- Would someone else know why you made it?

- What/who might represent your interests in this Data Lifeboat after you are no longer around?

- For whom are you saving these materials in the Data Lifeboat, and what do you want them to understand?

Conclusion: README as Cipher?

With these questions in mind, we have a unique opportunity to embed conscious curation, guided by C.A.R.E. and F.A.I.R. principles, into long-term digital preservation of Flickr.com. The README prompts Data Lifeboat creators to thoughtfully consider the ethical dimensions of their future collections.

This deliberate slowness or friction in the process is, we believe, a strength. However, it is equally important that writing a README is an enjoyable and engaging experience. Inventing a pleasant yet inquiring process will be central to the next phase of our work, where service design will play a key role. We will need to decide where to strike the balance between a README flow that is thought-provoking and poetic versus one that is instructive and immediately legible.

While the extent to which the README’s conditions can be made machine-readable remains an open question, there may be ways to encode conditions for use or distribution into the Data Lifeboat itself, or the Safe Harbor Network. It is essential to acknowledge, however, that a README is not a binding promise—it cannot guarantee the fulfilment of all wishes for all time. At the very least, it represents a thoughtful attempt to record the creator’s intentions.

The README serves as a cipher for future reception and reconstruction, a snapshot of the present, and a gift to future explorers.