From Desiderata to READMEs: The case for a C.A.R.E.-full Data Lifeboat Pt. I

By Fattori McKennaThis is the first of a two-part blog post where we detail our thinking around ethics and the Data Lifeboat README function. In this blog-post we reflect on the theoretical precursors and structural interventions that inform our approach. We specifically question how these dovetail with the dataset we are working with (i.e. images on Flickr.com) and the tool we’re developing, the Data Lifeboat. In part 2 (forthcoming), we will detail the learnings from our ethics session at the Mellon co-design workshops and how we plan to embed these into the README feature.

Spencer Baird, the American naturalist and first curator of the Smithsonian Institution, instructed his collectors in ‘the field’ what to collect, how to describe it and how to preserve it until returning back Eastwards, carts laden. His directions included:

Birds and mammalia larger than a rat should be skinned. For insects and bugs — the harder kinds may be put in liquor, but the vessels and bottles should not be very large. Fishes under six inches in length need not have the abdominal incision… Specimens with scales and fins perfect, should be selected and if convenient, stitched or pinned in bits of muslin to preserve the scales. Skulls of quadrupeds may be prepared by boiling in water for a few hours… A little potash or ley will facilitate the operation.

Baird’s 1848 General Directions for Collecting and Preserving Objects of Natural History is an example of a collecting guide, also known at the time as a desiderata (literally ‘desired things’). It is this archival architecture that Hannah Turner (2021) takes critical aim at in Cataloguing Culture: Legacies of Colonialism in Museum Documentation. According to Turner, Baird’s design “enabled collectors in the field and museum workers to slot objects into existing categories of knowledge”.

Whilst the desiderata prompted the diffuse and amateur spread of collecting in the 19th century, no doubt flooding burgeoning institutional collections with artefacts from the so-called ‘field’, the input and classification systems these collecting guides held came with their own risks. Baird’s 1848 desiderata shockingly includes human subjects—Indigenous people—perceived as extensions of the natural world and thus procurable materials in a concerted attempt to both Other and historicise. Later collecting guides would be issued for indigenous tribal artefacts, such as the Haíłzaqv-Haida Great Canoe – now in the American Museum of Natural History’s Northwest Coast Hall – as well as capturing intangible cultural artefacts – as documented in Kara Lewis’ study of the 1890 collection of Passamaquoddy wax recording cylinders used for tribal music and language. But Turner pivots our focus away from what has been collected, and instead towards how these objects were collected, explaining, “practices and technologies, embedded in catalogues, have ethical consequences”.

While many physical artefacts have been returned to Indigenous tribes through activist-turned-institutional measures (such as the repatriation of Iroquois Wampum belts from the National Museum of the American Indian or the Bååstede project returning Sami cultural heritage from Norway’s national museums), the logic of the collecting guides remains. Two centuries later, the nomenclature and classification systems from these collecting guides have been largely transposed into digital collection management systems (CMS), along with digital copies of the objects themselves. Despite noteworthy efforts to to provide greater access and transparency through F.A.I.R. principles or rewrite and reclaim archival knowledge systems—such as Traditional Knowledge (T.K.) Labels and C.A.R.E. principles, Kara Lewis (2024) notes that “because these systems developed out of the classification structures before them, and regardless of how much more open and accessible they become, they continue to live with the colonial legacies ingrained within them”. The slowness of the Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums (G.L.A.M.) sector to adapt, Lewis continues, stems less from “an unwillingness to change, and more with budgets that do not prioritize CMS customizations”. Evidently a challenge lies in the rigidly programmed nature of rationalising cultural description for computational input.

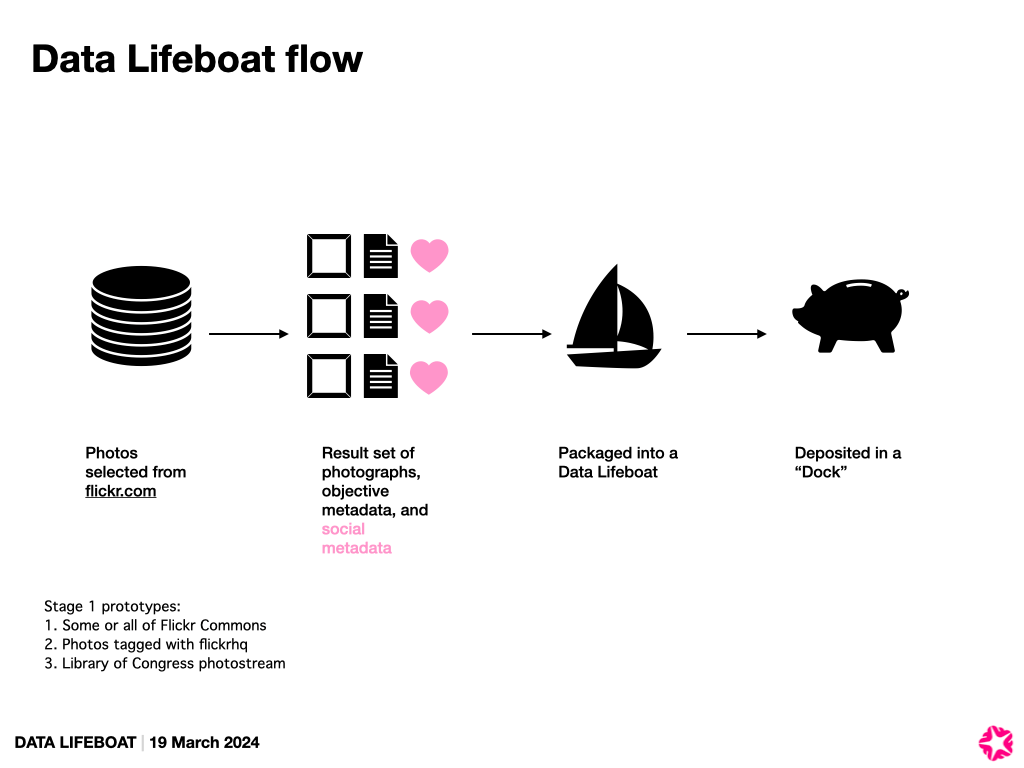

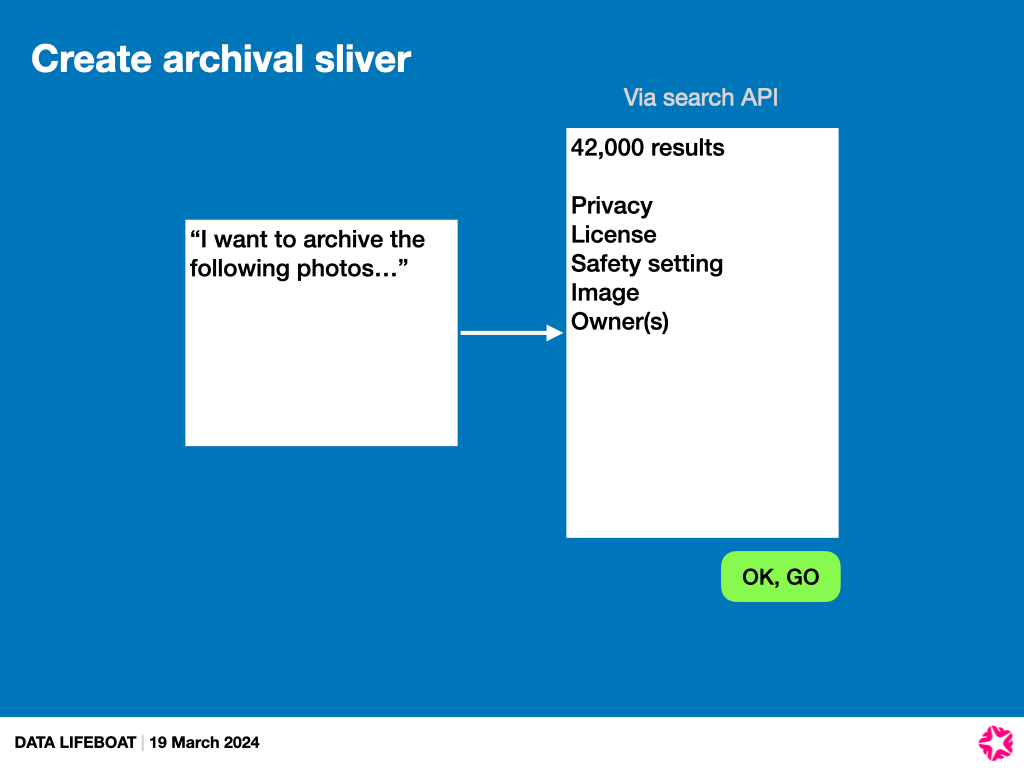

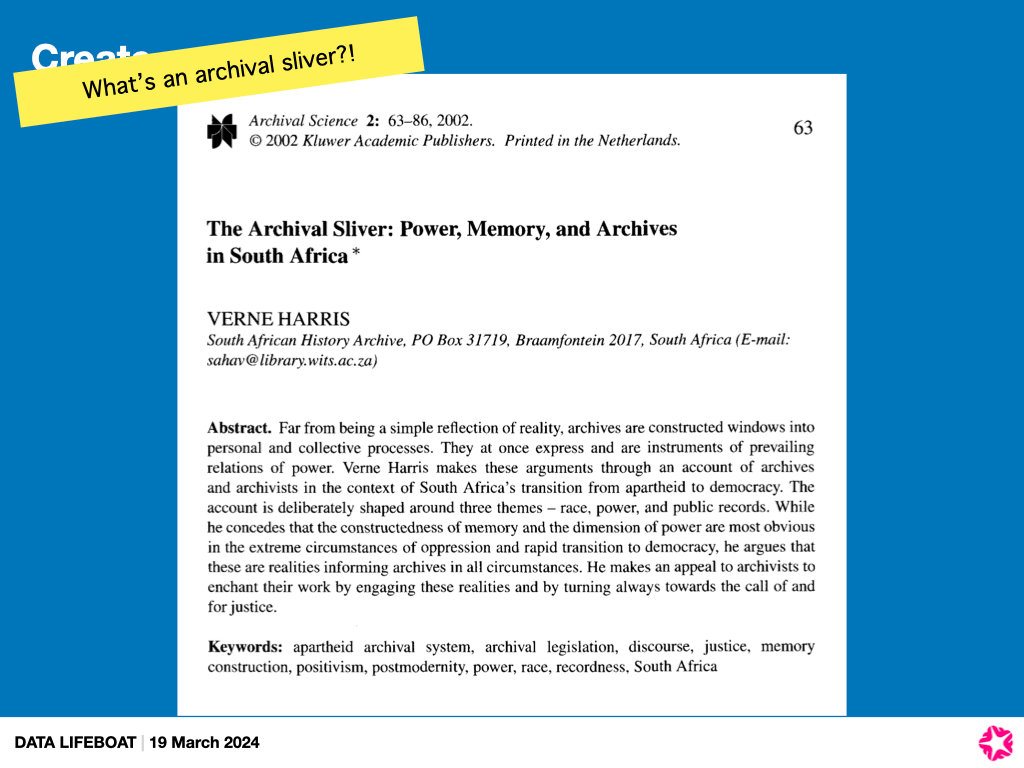

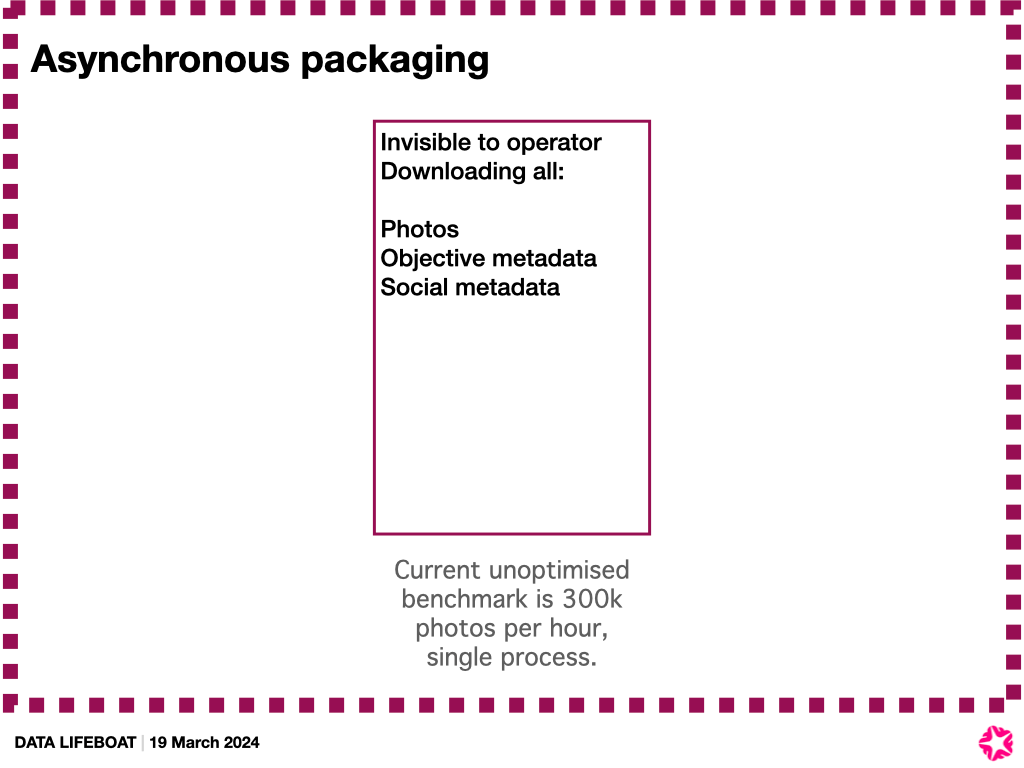

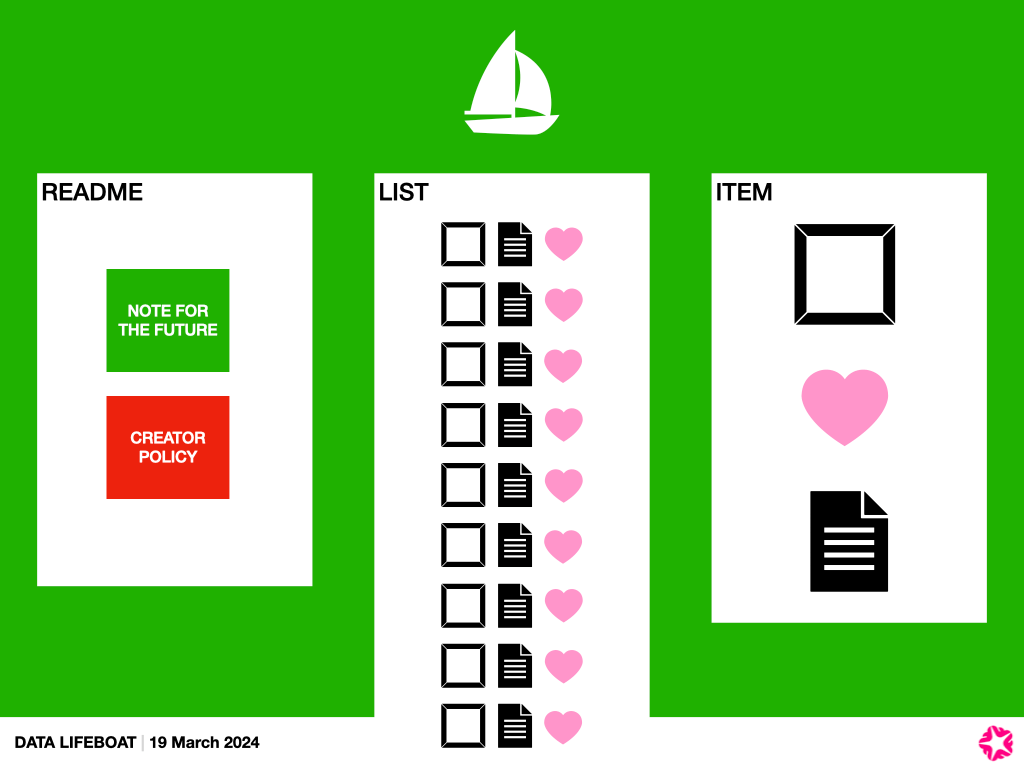

In our own Content Mobility programme, the Data Lifeboat project, we propose that creators write a README. In our working prototype, the input is an open-text field, allowing creators to write as much or as little as they wish about their Data Lifeboat’s purpose, contents, and future intentions. However, considering Turner’s cautionary perspective, we face a modern parallel: today’s desiderata is data, and the field is the social web—deceptively public for users to browse and “Right-Click-Save” at will. We realised that in designing the input architecture for Data Lifeboats, we could inadvertently be creating a 21st century desiderata: a seemingly open and neutral digital collecting tool that beneath the surface risks perpetuating existing inequalities.

This blog-post will introduce the theoretical and ethical underpinnings to the Data Lifeboat’s collecting guide, or README, that we want to design. The decades of remedy and reconciliatory work, tirelessly driven primarily by Indigenous rights activists, in addressing the archival injustices first cemented by early collecting guides provides a robust starting point for embedding ethics into the Data Lifeboat. Indigenous cultural heritage inevitably exists within Flickr’s collections, particularly among our Flickr Commons members who are actively pursuing their own reconciliation initiatives. Yet the value of these interventions extends beyond Indigenous cultural heritage, serving as a foundation for ethical data practices that benefit all data subjects in the age of Big Data.

A Brief History of C.A.R.E Principles

Building on decades of Indigenous activism and scholarship in restitution and reconciliation, the C.A.R.E. principles emerged in 2018 from a robust lineage of interventions, such as Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA, 1990) and The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP, 2007), which sought to recognise and restore Indigenous sovereignty over tangible and intangible cultural heritage.

These earlier frameworks were primarily rooted in consultation processes with Indigenous communities, ensuring that their consent and governance shaped the management of artefacts and knowledge systems. For instance, NAGPRA enabled tribes to reclaim human remains and sacred objects through formalised dialogues and consultation sessions with museums. Similarly, Traditional Knowledge Labels (Local Contexts Initiative) were designed to identify Indigenous protocols for accessing and using knowledge within the museum’s existing collection, for instance a tribal object may be reserved for viewing only by female tribal members. These methods worked effectively within the domain of physical collections but faltered when confronted with the scale and opaqueness of data in the digital age.

In this context, Indigenous governance of data emerged as essential, particularly for sensitive datasets such as health records, where documented misuse showed evidence of perpetuating harm. As the Data Science field developed, it often prioritised the technical ideals of F.A.I.R. principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable), which advocate for improved usability and discoverability of data, to counter increasingly oblique and privatised resources. Though valuable, F.A.I.R. principles fell short on the ethical dimensions of data, particularly on how data is collected and used in ways that affect already at-risk communities (see also O’Neil 2016, Eubanks 2018, and Benjamin 2019). As the Global Indigenous Data Alliance argued:

“Mainstream values related to research and data are often inconsistent with Indigenous cultures and collective rights”

Recognising the challenges posed by Big Data and Machine Learning (ML)—from entrenched bias in data to the opacity of ML algorithms—Indigenous groups such as the Te Mana Raraunga Māori Data Sovereignty Network, the US Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network, and the Maiam nayri Wingara Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Data Sovereignty Collective led efforts to articulate frameworks for ethical data governance. These efforts culminated in a global, inter-tribal workshop in Gaborone, Botswana, in 2018, convened by Stephanie Russo Carroll and Maui Hudson in collaboration with the Research Data Alliance (RDA) International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group. The workshop formalised the C.A.R.E. principles, which were published by the Global Indigenous Data Alliance in September 2019 and proposed as a governance framework with people and purpose at its core.

The C.A.R.E. principles foreground the following four values around data:

- Collective Benefit: Data must enhance collective well-being and serve the communities to which it pertains.

- Authority to Control: Communities must retain governance over their data and decide how it is accessed, used, and shared.

- Responsibility: Data handlers must minimise harm and ensure alignment with community values.

- Ethics: Ethical considerations rooted in cultural values and collective rights must guide all stages of the data lifecycle.

C.A.R.E. in Data Lifeboats?

While the C.A.R.E. principles were initially developed to address historical data inequities and exploitation faced by Indigenous communities, they offer a framework that can benefit all data practices: as the Global Indigenous Data Alliance argues, “Being CARE-Full is a prerequisite for equitable data and data practices.”

We believe the principles are important for Data Lifeboat, as collecting networked images from Flickr poses the following complexities:

- Data Lifeboat creators will be able to include images from Flickr Commons members (which may include images of culturally sensitive content)

- Data Lifeboat creators may be able to include images from other Flickr members, besides themselves

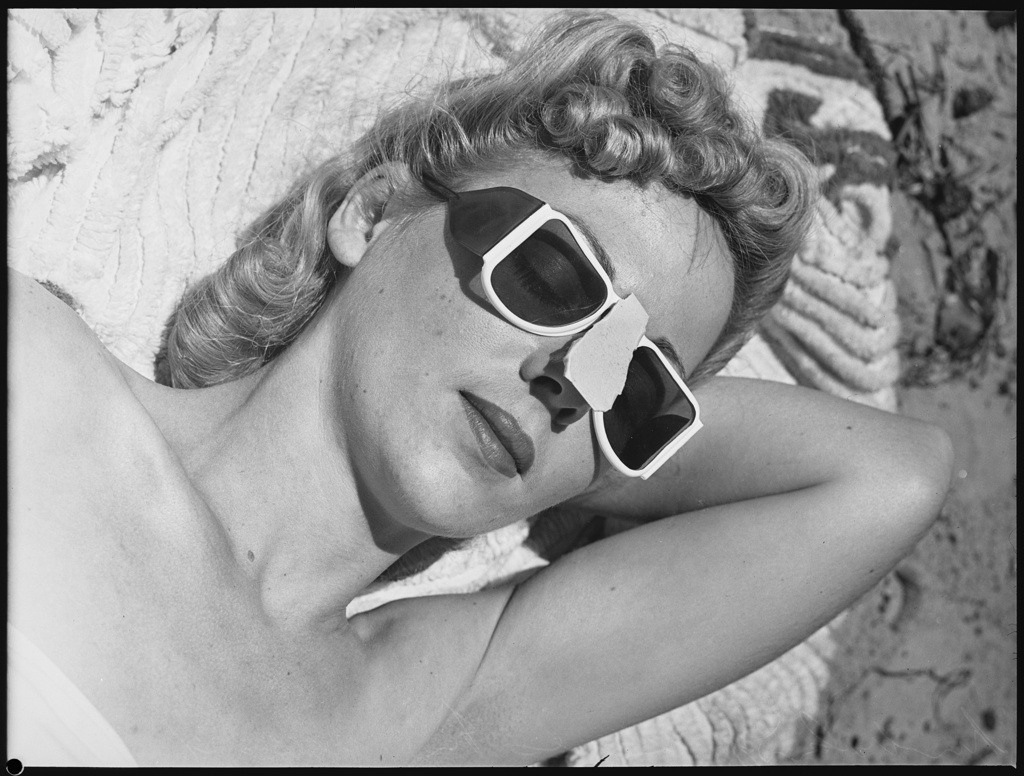

- Subjects of photographs in a Data Lifeboat may be from historically at-risk groups

- Data Lifeboats are designed to last and therefore may be separated from their original owners, intents and contexts.

The Global Inidgenous Data Alliance asserts, their principles must guide every stage of data governance “from collection to curation, from access to application, with implications and responsibilities for a broad range of entities from funders to data users.” The creation of a Data Lifeboat is an opportunity to create a new collection, thus we have the opportunity to embed C.A.R.E. principles from the start. Although we cannot control how Data Lifeboats will be used or handled after their creation, we can attempt to establish an architecture for encouraging that C.A.R.E. is deployed throughout the data lifecycle.

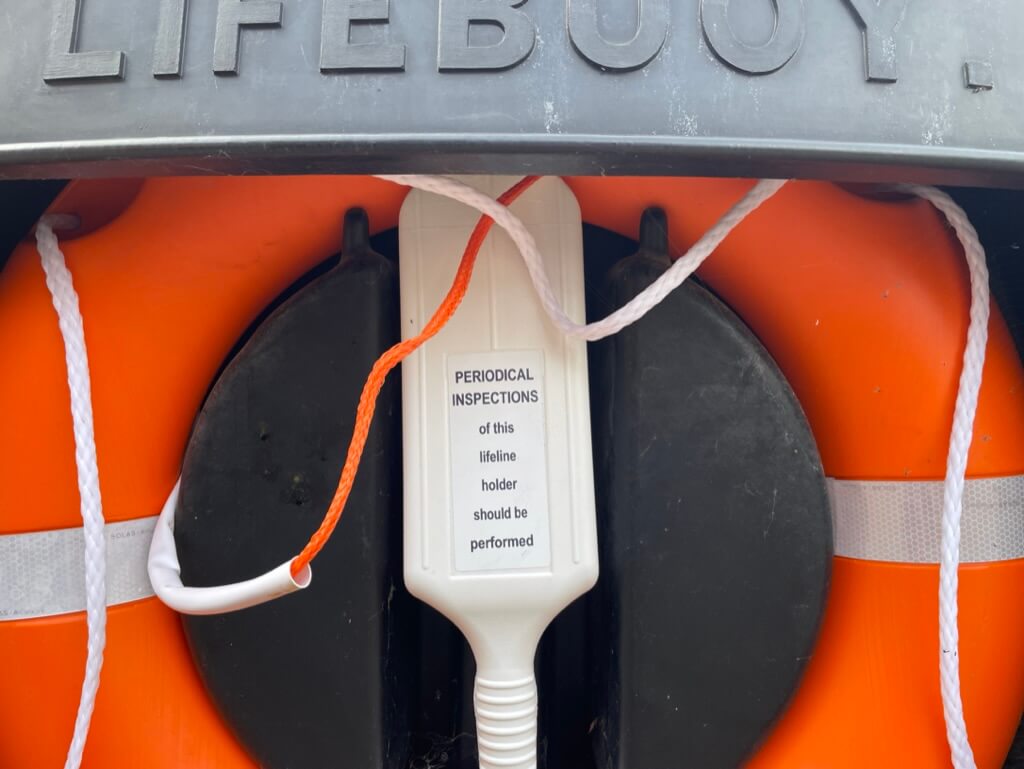

Enter: The README

Our ambition for the Data Lifeboat (and the ethos behind many of Flickr.org programmes) is the principle of “conscious collecting”. We aim to move away from the mindset of perpetual accumulation that plagues both museums and Big Tech alike—a mindset that advances a dangerous future, as cautioned by both anti-colonialist and environmentalist critiques. Conscious collecting allows us to better consider and care for what we already have.

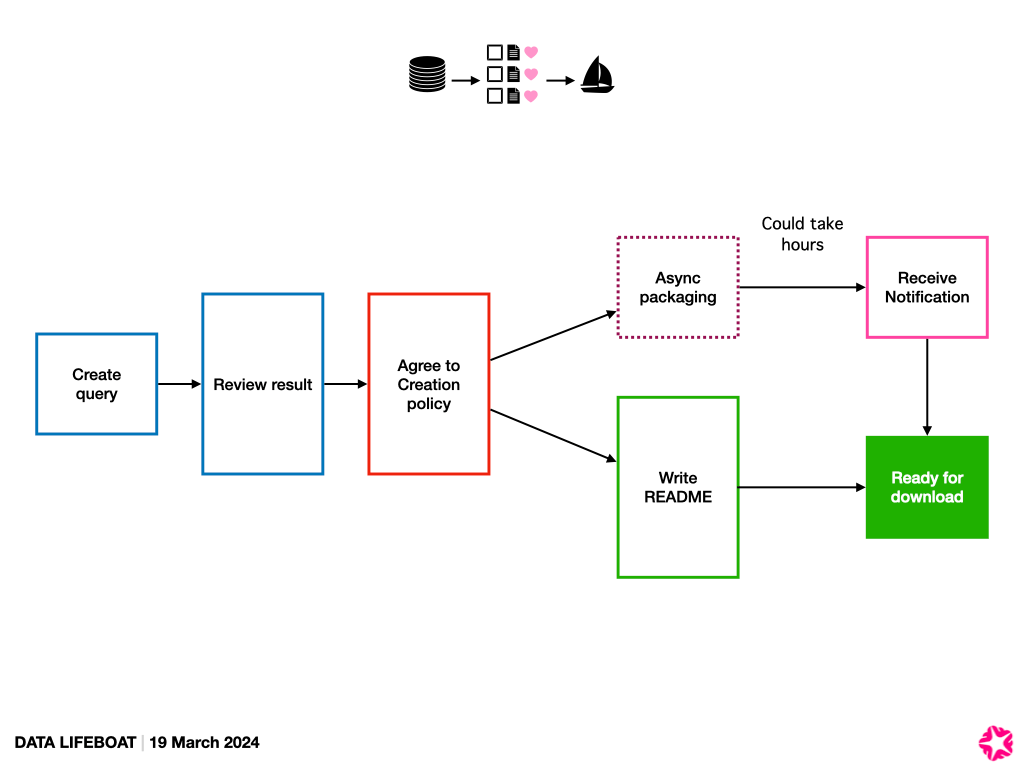

One of the possible ways we can embed conscious collecting is through the inclusion of a README—a reflective, narrative-driven process for creating a Data Lifeboat.

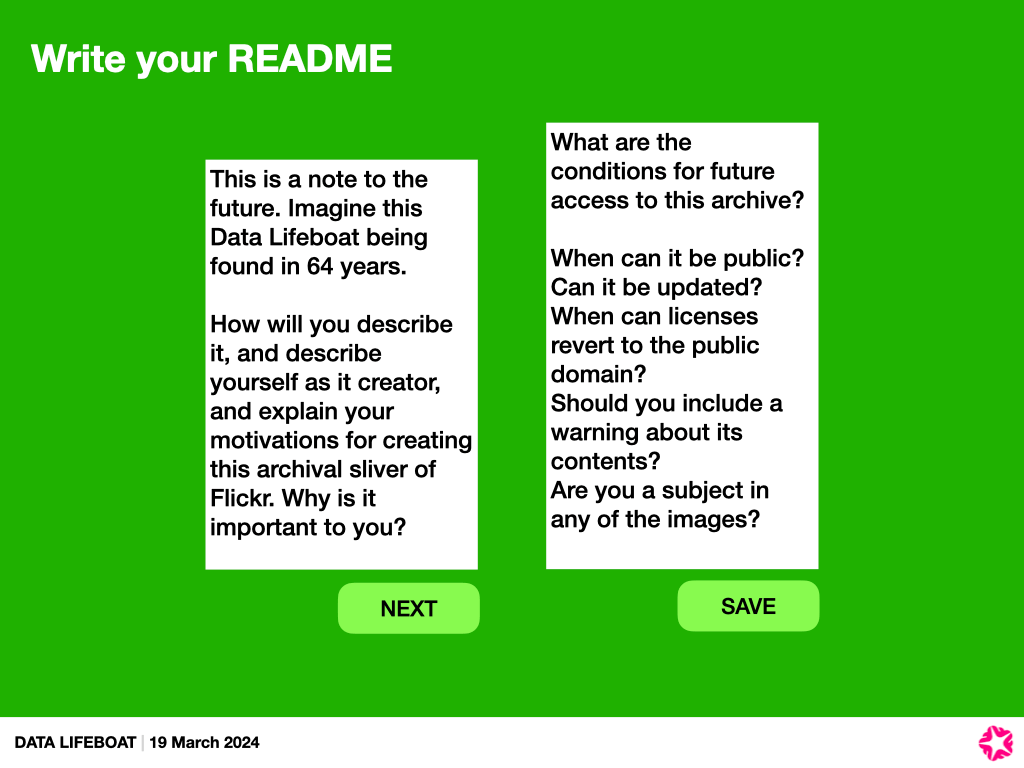

READMEs are files traditionally used in software development and distribution that contain information about files within the directory. It is often in the form of plain text (.txt, .md), to maximise readability, frequently containing information about operating instructions, troubleshooting, credits, licensing and changelogs, intended to be read on start-up. In the Data Lifeboat, we have adopted this container to supplement the files. Data Lifeboat creators are introduced to the README in the creation process and, in the present prototype, are met with the following prompts to assist writing:

- Tell the future why you are making this Data Lifeboat.

- Is there anything special you’d like future viewers to know about the contents? Anything to be careful about?

(These prompts are not fixed, as you’ll read in Part 2)

During our workshops, participants noted the positive (and rarely seen) experience of introducing friction to data preservation. This friction slows down the act of collecting and creates space to engage with the social and ethical dimensions of the content. As Christen & Andersen (2019) emphasise in their call for Slow Archives, “Slowing down creates a necessary space for emphasising how knowledge is produced, circulated, and exchanged through a series of relationships”. We hope that Data Lifeboat’s README will contribute to Christen & Andersen’s invocation for the “development of new methodologies that move toward archival justice that is reparative, reflective, accountable, and restorative”.

We propose three primary functions of the README in a Data Lifeboat:

-

Telling the Story of an Archive

Boast, Bravo, and Srinivasan (2018), reflecting on Inuit artefacts in an institutional museum collection, write that its transplant results in the deprivation of “richly situated life of objects in their communities and places of origin.” Once subsumed into a collection, artefacts often suffer the “loss of narrative and thick descriptions when transporting them to distant collections”.

We are conscious that this could be the fate of many images once transplanted in a Data Lifeboat. Questions emerged in our workshops as to how to maintain the contextual world around the object, speaking of not only its social metadata (comments, tags, groups, albums) but also the more personal levers of choice, value and connection. A README resists the diminishment of narrative by creating opportunities to retain and reflect on the relational life of the materials.

The README directly resists the archival instinct toward neutrality, by its very format it holds that this can never be true. Boden critiques the paucity of current content management systems, their highly structured input formats cannot meet our responsibilities to communities as they do not give space to fully citing how information came to be known and associated with an object and on whose authority. Boden argues for “reflections on the knowledge production process”, which is what we intend the README to encourage the Data Lifeboat creator to do. The README prompts (could) suggest Data Lifeboat creator reflect on issues around ownership (e.g. is this your photo?), consent (e.g. were all photo subjects able to consent to inclusion in a Data Lifeboat?), and embedded power relations (e.g. are there any persecuted minorities in this Data Lifeboat?): acknowledging the archive is never objective.

More poetically, the README could prompt greater storytelling, serving as a canvas for both critical and emotional reflection on the content of a Data Lifeboat. Through guided prompts, creators could explore their personal connections to the images, share the stories behind their selection process, and document the emotional resonance of their collection. A README allows creators to capture and contextualise not only the images themselves, but to add layers of personal inscription and meaning, creating a richer, more distributed archive.

-

Decentralised and Distributed Annotation

The Data Lifeboat constitutes a new collecting format that intends to operate outside traditional archival systems’ rigid limitations and universalising classification schemes. The README encourages decentralised curation and annotation by enabling communities to directly contribute to selecting and contextualising archival and contemporary images, fostering what Huvila (2008) terms the ‘participatory archive’ [more on Data Lifeboat as a tool for decentralised curation here].

User-generated descriptions such as comments, tags, groups, and galleries — known on Flickr as ‘social metadata’ —serve as “ontological keys that unlock the doors to diverse, rich, and incommensurable knowledge communities” (Boast et al., 2018), embracing multiple ways of knowing the world. Together, these create ‘folksonomies’—socially-generated digital classification systems that David Sturz argues are particularly well-suited to “loosely-defined, developing fields,” such as photo subjects and themes often overlooked by the institutional canon. The Data Lifeboat captures the rich, social media that is native to Flickr, preserving decades worth of user contributions.

The success of community annotation projects has been well-documented. The Library of Congress’s own Flickr Pilot Project demonstrated how community input enhanced detail, correction, and enrichment. As Michelle Springer et al. (2018) note, “many of our old photos came to us with very little description and that additional description would be appreciated”. Within nine months of joining Flickr, committing to a hands-off approach, the Library of Congress accumulated 67,000 community-added tags. “The wealth of interaction and engagement that has taken place within the comments section has resulted in immediate benefits both for the Library and users of the collections,” continues Springer et al. After staff verification, these corrections and additions to captions and titles demonstrated how decentralised annotation could reshape the central archive itself. As Laura Farley (2014) observes, community annotation “challenges archivists to see their collections not as closely guarded property of the repository, but instead as records belonging to a society of users”.

Beyond capturing existing metadata, the README enables Data Lifeboat creators to add free-form context, such as correcting erroneous tags or clarifying specific terminology that future viewers might misinterpret—like the Portals to Hell group. As Duff and Harris (2002) write, “the power to describe is the power to make and remake records and to determine how they will be used and remade in the future. Each story we tell about our records, each description we compile, changes the meaning of records and recreates them” — the README hands over the narrative power to describe.

-

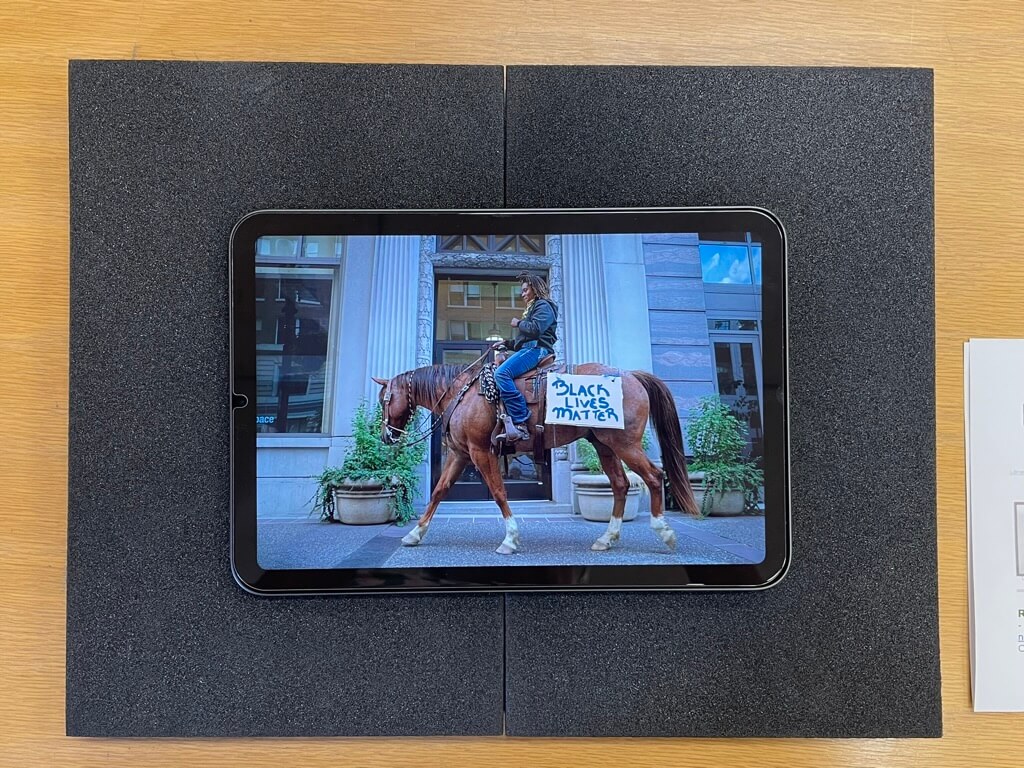

Data Restitution and Justice

Thinking speculatively, the README could serve an even more transformative purpose as a tool for digital restitution. Through the Data Lifeboat framework, communities could reclaim contested archival materials and reintegrate them into their own digital ecosystems. This approach aligns with “Steal It Back” (Rivera-Carlisle, 2023) initiatives such as Looty, which creates digital twins of contested artefacts, currently held in Western museums. By leveraging digital technologies, these initiatives counter the slow response of GLAM institutions to restitution calls. As Pavis and Wallace (2023) note, digital restitution offers the chance to “reverse existing power hierarchies and restore power with the peoples, communities, and countries of origin”. In essence, this offers a form of “platform exit” that carves an alternative avenue of control of content to original creators or communities, regardless of who initially uploaded the materials. In an age of encroaching data extractivism, the power to disengage, though severe, for at-risk communities can be the “reassertion of autonomy and agency in the face of pervasive connectivity” (Kaun and Treré, 2021).

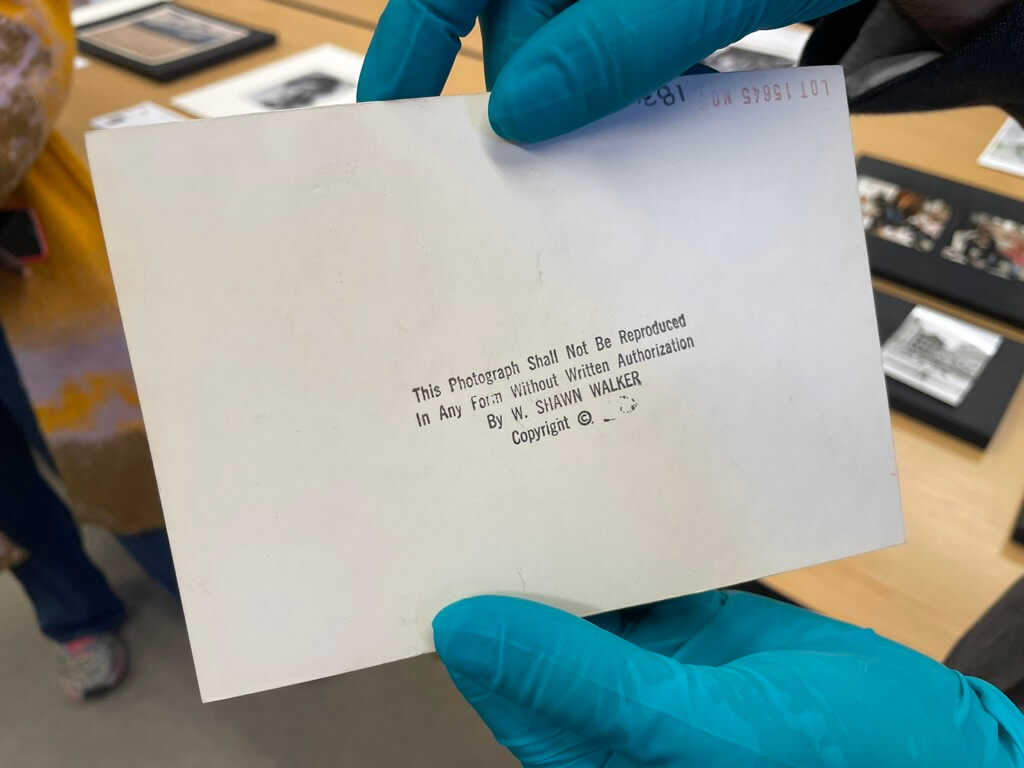

It is a well-documented challenge in digital archives that many of the original uploaders were not the original creators, which prompts ought to prompt reflections around copyright and privacy. As Payal Arora (2019) has noted our dominant frameworks largely ignore empirical realities of the Global South: “We need to open our purview to alternative meanings including paying heed to the desire for selective visibility, how privacy is often not a choice, and how the cost of privacy is deeply subjective”. Within the README, Data Lifeboat creators can establish terms for their collections, specifying viewing contexts, usage conditions, and other critical contextual information. They can also specify restrictions on where and how their images may be hosted or reused in the future (e.g. ‘I refuse to let these image be used in AI training data sets’). A README could allow for Data Lifeboat creators to expand and detail more fluid and cultural and context-specific conditions for privacy and re-use.

At best, these terms would allow Data Lifeboat creators to articulate their preferences for how their materials are accessed, interpreted and reused in the future, functioning as an ethical safeguard. While these terms may not always be enforceable, they provide a clear record of the creators’ intentions. Looking ahead, we could envision the possibility of making these terms machine-readable and executable. The sustenance of these terms could potentially be incorporated into the governance framework of the Safe Harbor Network, our proposed decentralised storage system of cultural institutions that can hold Data Lifeboats for the long-term.

Discussion: README as a Datasheet for Networked Social Photography Data Sets?

In the long history of cataloging and annotating data, Timnit Gebru et al.’s (2018) Datasheets for Datasets stands out as an emerging best practice for the machine learning age. These datasheets provide “a structured approach to the description of datasets,” documenting provenance, purpose, and ethical considerations. By encouraging creators to critically reflect on the collection, composition, and application of datasets, datasheets foster transparency and accountability in an otherwise vast, opaque, and voraciously consuming sphere.

The Digital Cultural Heritage space has made similar calls for datasheets in archival contexts, as they too handle large volumes of often uncontextualised and culturally sensitive data. As Alkemade et al. (2023) note, cultural heritage data is unique: “They are extremely diverse by nature, biased by definition and hardly ever created or collected with computation in mind”. They argue, “In contrast to industrial or research datasets that are assembled to create knowledge… cultural heritage datasets may present knowledge as it was fabricated in earlier times, or community-based knowledge from lost local contexts”. Given this uniqueness, digital cultural heritage requires a tailored datasheet format that enables rich, detailed contextualization reflecting both the passage of time and potentially lost or inaccessible meanings. Just as datasheets have transformed technical datasets, the README has the potential to reshape how we collect, interpret, and preserve the networked social photography that is native to the Flickr.com platform — something we argue is part of our collective digital heritage.

There are, of course, limitations—neither datasheets nor READMEs will be a panacea for C.A.R.E-full data practices. Gebru et al. acknowledge that “Dataset creators cannot anticipate every possible use of a database”. The descriptive approach also presents possible trade-offs: “identifying unwanted societal biases often requires additional labels indicating demographic information about individuals,” which may conflict with privacy or data protection. Gebru notes that the Datasheet “will necessarily impose overhead on dataset creator”—we recognise this friction as a positive. Echoing Christen and Anderson’s call “Slowing down is about focusing differently, listening carefully, and acting ethically“.

Conclusion

Our hope is that the README is both a reflective and instructive tool that prompts Data Lifeboat Creators to consider the needs and wishes of each of the four main user groups in the Data Lifeboat ecosystem:

- Flickr Members

- Data Lifeboats Creators

- Safe Harbor Dock Operators

- Subjects in the Photo

While we do not yet know precisely what form the README will take, we hope our iterative design process can offer flexibility to accommodate the needs of—and our responsibilities to—Data Lifeboat creators, photographic subjects and communities, and future viewers.

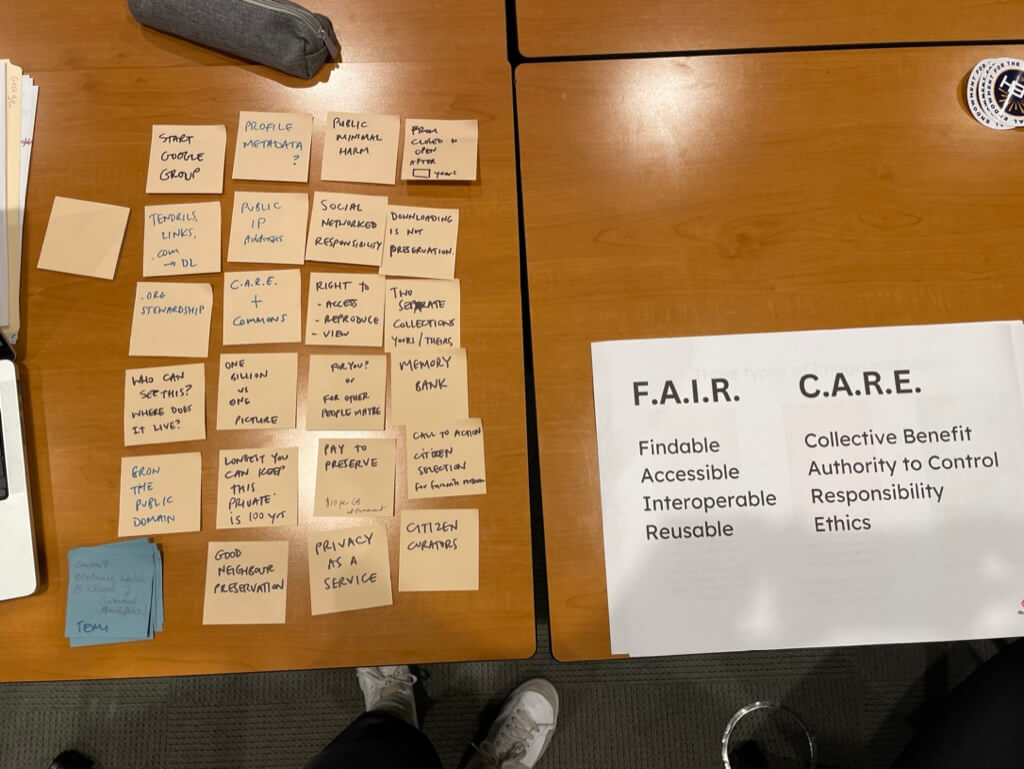

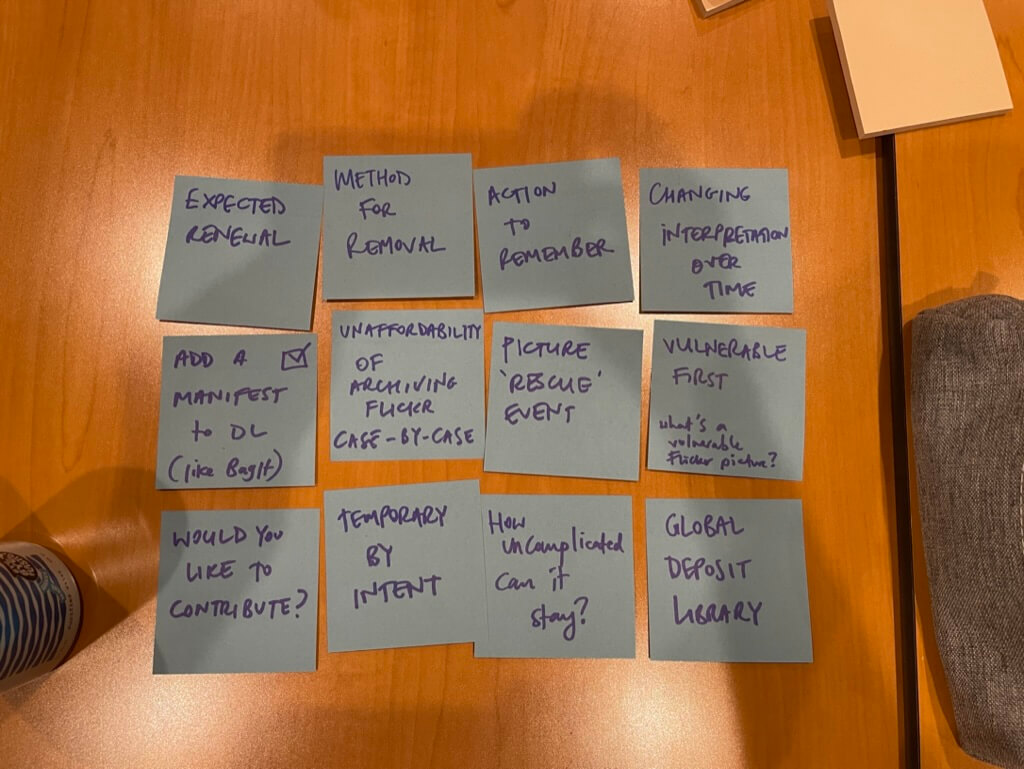

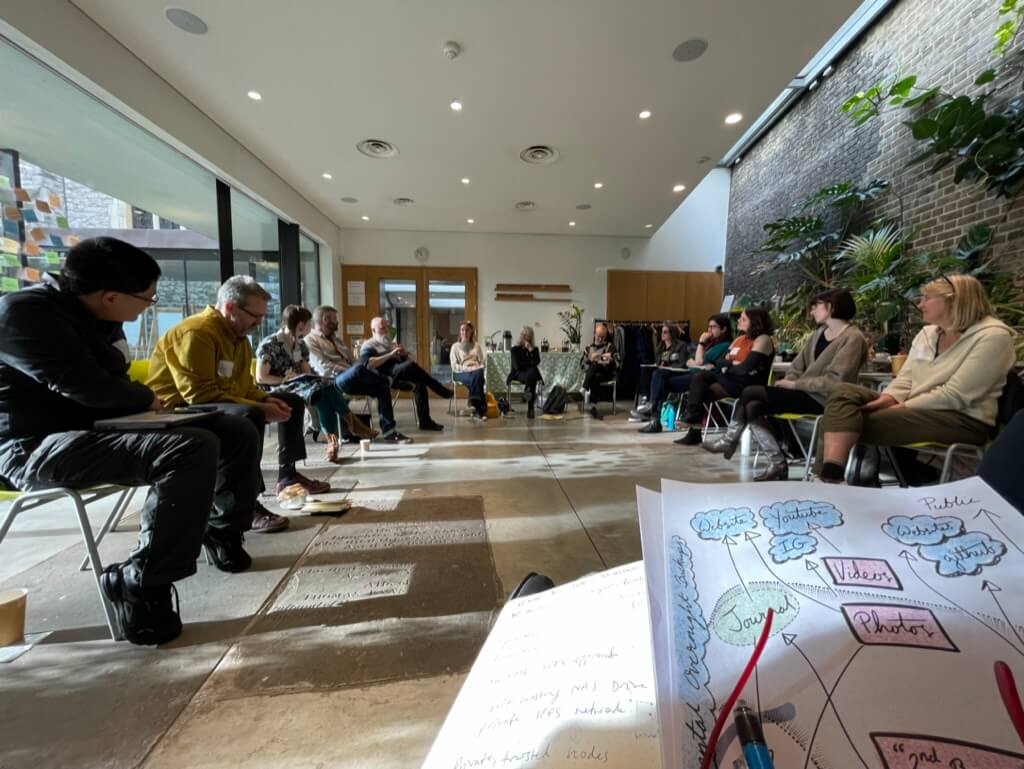

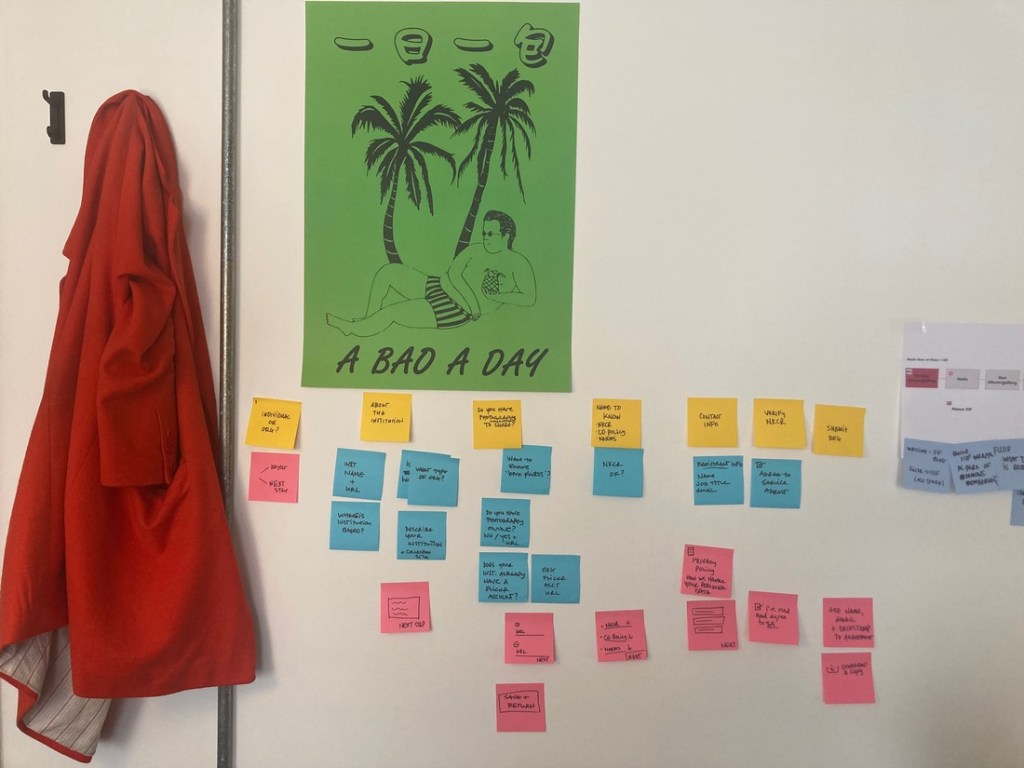

In our Mellon-funded Data Lifeboat workshops in October and November, we asked our participants to support us in co-designing a digital collecting tool with care in mind. We asked:

What prompts or questions for Data Lifeboat creators could we include in the README to help them think about C.A.R.E. or F.A.I.R. principles. Try to map each question to a letter.

The results of this exercise and what this means for Data Lifeboat development will be detailed in Part 2.

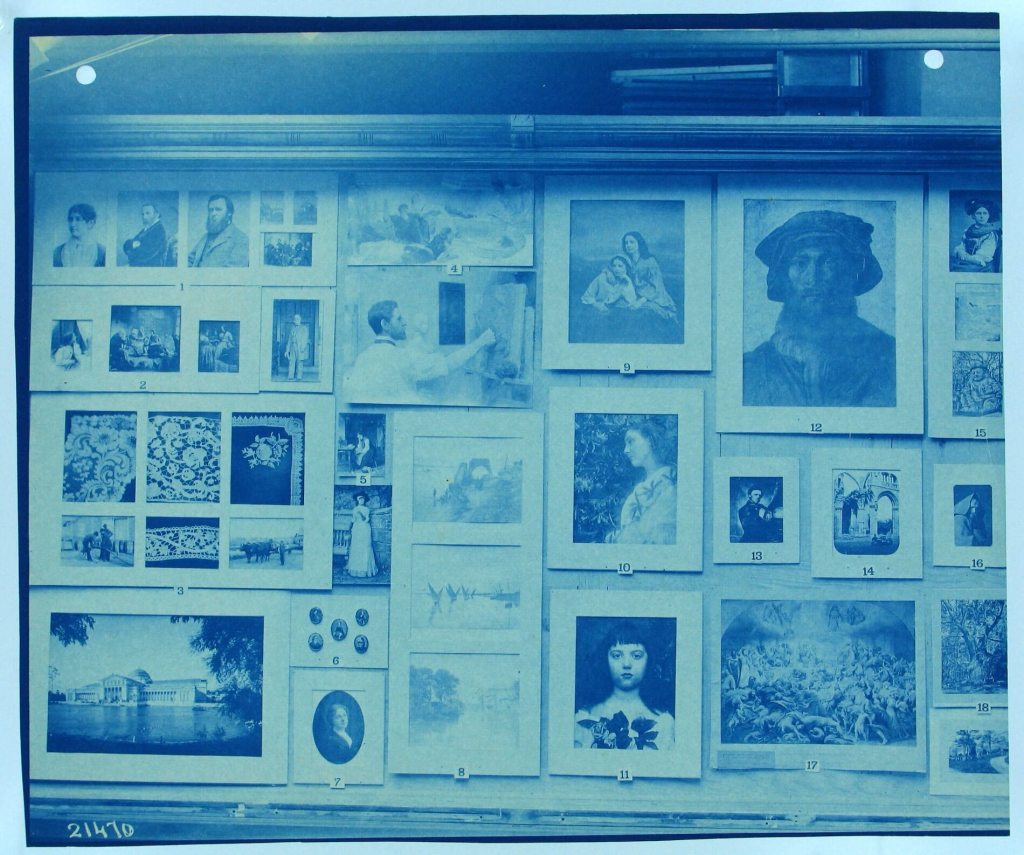

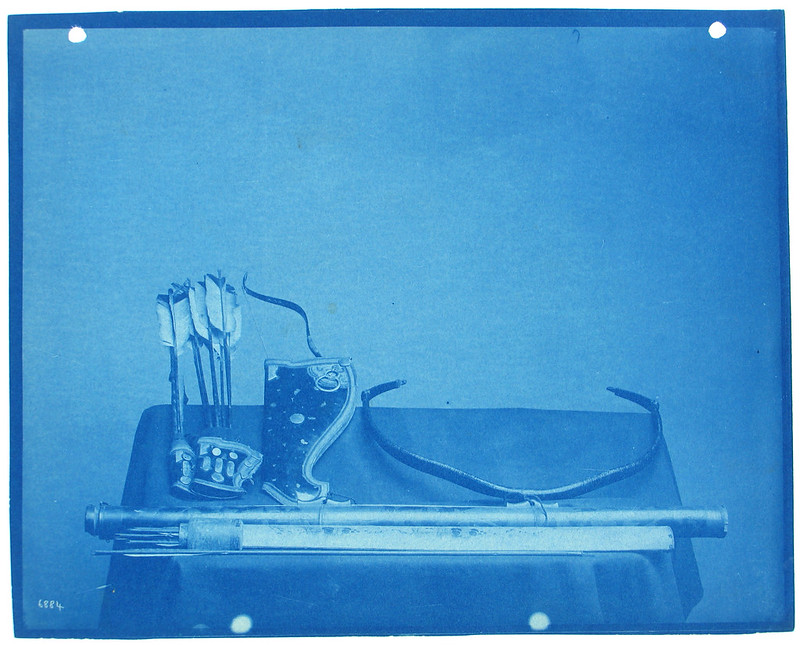

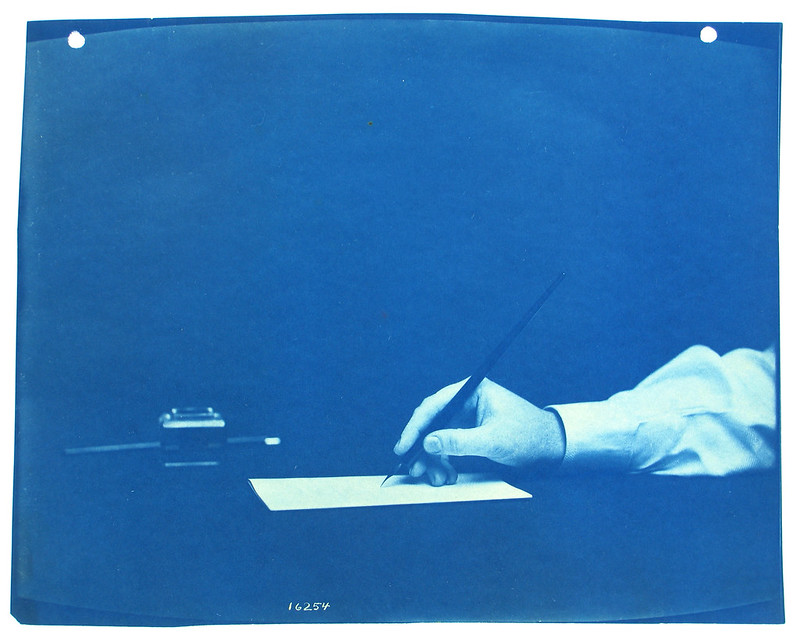

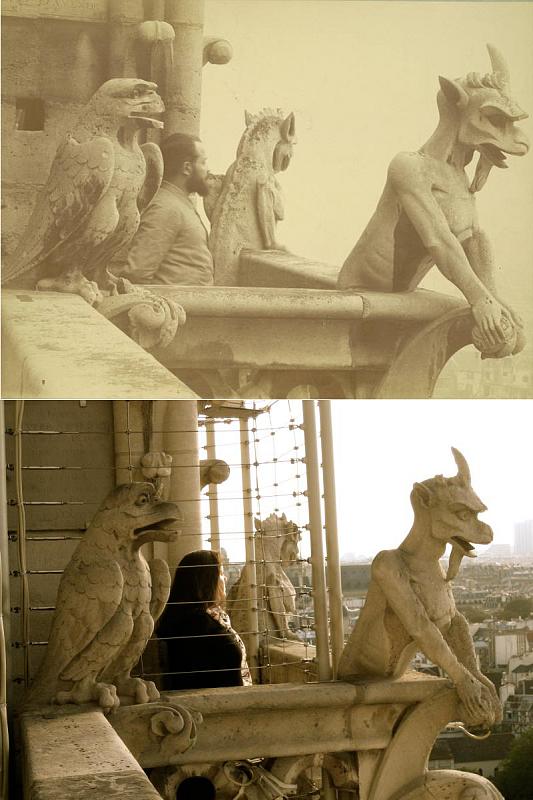

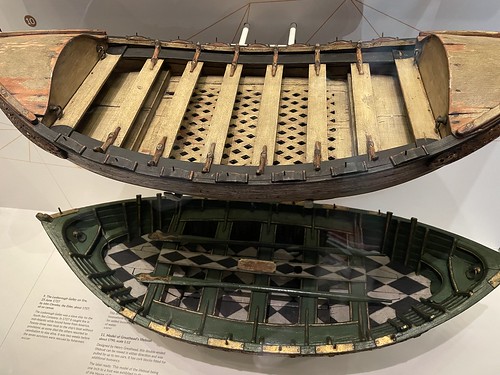

The photographs in this blog post come from the Smithsonian Institution’s Thomas Smillie Collection (Record Unit 95) – Thomas Smillie served as the first official photographer for the Smithsonian Institution from 1870 until his death in 1917. As head of the photography lab as well as its curator, he was responsible for photographing all of the exhibits, objects, and expeditions, leaving an informal record of early Smithsonian collections.

Bibliography

Alkemade, Henk, et al. “Datasheets for Digital Cultural Heritage Datasets.” Journal of Open Humanities Data, vol. 9, 2023, doi:10.5334/johd.124.

Arora, Payal. “Decolonizing Privacy Studies.” Television & New Media, vol. 20, no. 4, 26 Oct. 2018, pp. 366–378, doi:10.1177/1527476418806092.

Baird, Spencer. “General Directions for Collecting and Preserving Objects of Natural History”, c. 1848, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections

Benjamin, Ruha. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity, 2019.

Boast, Robin, et al. “Return to Babel: Emergent Diversity, Digital Resources, and Local Knowledge.” The Information Society, vol. 23, no. 5, 27 Sept. 2007, pp. 395–403, doi:10.1080/01972240701575635.

Boden, Gertrud. “Whose Information? What Knowledge? Collaborative Work and a Plea for Referenced Collection Databases.” Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals, vol. 18, no. 4, 12 Oct. 2022, pp. 479–505, doi:10.1177/15501906221130534.

Carroll, Stephanie Russo, et al. “The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance.” Data Science Journal, vol. 19, 2020, doi:10.5334/dsj-2020-043.

Christen, Kimberly, and Jane Anderson. “Toward Slow Archives.” Archival Science, vol. 19, no. 2, 1 June 2019, pp. 87–116, doi:10.1007/s10502-019-09307-x.

“Digital Media Activism A Situated, Historical, and Ecological Approach Beyond the Technological Sublime.” Digital Roots, by Emiliano Treré and Anne Kaun, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2021.

Duff, Wendy M., and Verne Harris. “Stories and Names: Archival Description as Narrating Records and Constructing Meanings.” Archival Science, vol. 2, no. 3–4, Sept. 2002, pp. 263–285, doi:10.1007/bf02435625.

Eubanks, Virginia. Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. Picador, 2018.

Gebru, Timnit, et al. “Datasheets for Datasets.” Communications of the ACM, vol. 64, no. 12, 19 Nov. 2021, pp. 86–92, doi:10.1145/3458723.

Griffiths, Kalinda E et al. “Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Data Governance in Health Research: A Systematic Review.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 18,19 10318. 30 Sep. 2021, doi:10.3390/ijerph181910318

Lewis, Kara. “Toward Centering Indigenous Knowledge in Museum Collections Management Systems.” Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals, vol. 20, no. 1, Mar. 2024, pp. 27–50, doi:10.1177/15501906241234046.

O’Neil, Cathy. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. Penguin, 2017.

Rivera-Carlisle, Joanna. “Contextualising the Contested: XR as Experimental Museology.” Herança, vol. 6, no. 1, 2023, doi.org/10.52152/heranca.v6i1.676

Pavis, Mathilde, and Andrea Wallace. “Recommendations on Digital Restitution and Intellectual Property Restitution.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2023, doi:10.2139/ssrn.4323678.

Schaefer, Sibyl. “Energy, Digital Preservation, and the Climate: Proactively Planning for an Uncertain Future.” iPRES 2024 Papers – International Conference on Digital Preservation. 2024.

Shilton, Katie, and Ramesh Srinivasan. “Participatory Appraisal and Arrangement for Multicultural Archival Collections.” Archivaria, vol. 63, Spring 2007.

Springer, Michelle et al. “For the Common Good: The Library of Congress Flickr Pilot Project”. Library of Congress Collections, 2008.

Sturz, David N. “Communal Categorization: The Folksonomy”, INFO622: Content Representation, 2004.

Turner, Hannah. Cataloguing Culture: Legacies of Colonialism in Museum Documentation. University of British Columbia Press, 2022.