Last week I attended the Born-Digital Collections, Archives & Memory conference, led by the School of Advanced Study at the University of London. It was a pleasure to hear about real-world experiences of born-digital collecting, how these ephemeral, unbounded objects enter, subsist and evolve in our collections, sometimes defining (and defying) the very nature of the collecting infrastructures themselves. These considerations are something we grapple with at the Flickr Foundation everyday.

Some personal highlights and reflections from the conference are as follows:

Dorothy Berry’s Keynote

Dorothy Berry, Digital Curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, delivered a stunning keynote that has sat with me for days. ‘Looking Back Through Opaque Glasses: What Born Digital Archives Can Learn from Analogue’ offered profound insights (set against stirring photographs) on the imperfect translation of memory from analogue to digital realms. Berry proposed that we view this murky transition as an opportunity to re-examine the digital archive’s purpose and practice.

Unlike digital archives, which attempt to preserve fixed material from specific moments in time, human memory functions in a fundamentally different manner. Each time we recall a memory, we actively reconstruct it. Memory is unstable but it is also richly associative, in forming connections and generative, in building itself anew each time. Perhaps it is not the remit of the archivist to attempt to mimic human memory in digital memory, yet as archival workers we might think about how, with all our new shiny tools in place, we can better honour memory’s inherent dynamism and personal nature.

Memories are more dynamic than any archive imaginable, they are also more easily destroyed – Dorothy Berry

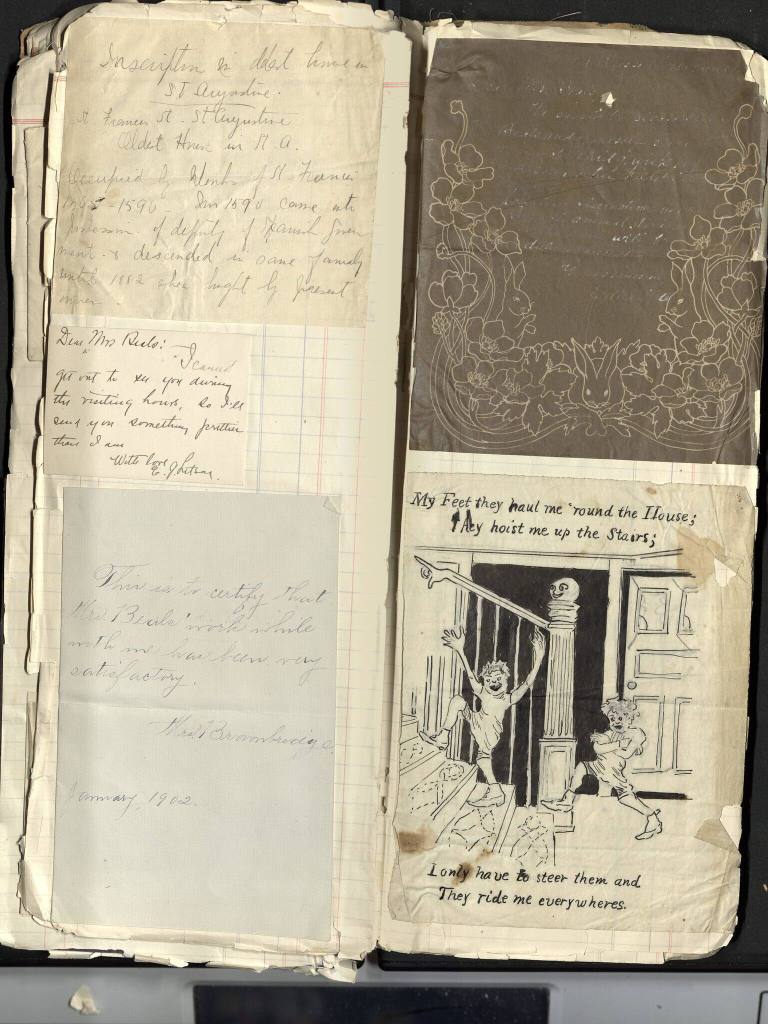

The fluid quality of memory stems from its inherent self-determination. As Berry aptly stated, “the things that we choose to keep are things that we choose”. Yet what enters today’s digital archives often bypasses our conscious selection as we scatter countless digital traces daily. My Pinterest boards, while not explicitly connected to my identity, will nonetheless feed into a future algorithmic memory, distributed and murky. Unlike analogue scrapbooks that I might deliberately curate, these digital collections exist in a paradoxical state, simultaneously mine yet beyond my control. Critically, as Berry pointed out, “Memory has not always wanted archives to make them permanent”. Whether I choose to donate my scrapbooks, or hand them down to future generations, is precisely this self-determining act, I have chosen what I am willing to make permanent. The digital archive remains indifferent to who I am or what I genuinely wish to preserve, as such, this principle of self-determination — so natural to human memory — should also be guiding principle of digital archiving.

Berry’s vision of digital memory’s future emerges as even more haunting in her stark metaphor: “When I see the future of digital preservation… I see hulked prison ships with limited options for liberation…” This powerful image speaks directly to the platformisation of our collective digital memory — corporate walled gardens that constrain not only archivists’ work but also our fundamental ability to reconstitute, revise, or revoke our own memories. At the Flickr Foundation, we envision an alternative through our Data Lifeboat initiative, designed to counter this prison-ship reality. Our approach aims to provide people with tools to engage with their social media traces in the same deliberate, meaningful way they might interact with physical scrapbooks — creating spaces that honour self-direction, enable reflective annotation, celebrate the unexpected connections and preserve the inherent joy of personal curation.

Other notable mentions:

- The Science Museum’s learnings from ingesting social media for the first time. I was reminded of the beloved ‘Absolute Unit’ post of a photograph of an Exmoor ram from 1962, that spurred thousands of engagements and the posting many other “units”. It remains one of the most significant and famous examples of meme culture in the UK. For years this was bouncing around internal servers, a clear issue of digital content not fitting pre-existing DAMS categories. Furthermore what’s presented as a ‘bounded object’ in the WARC file, in reality it has “fuzzy edges”. It is the complex decision of the digital archivist to determine the limits to these edges, whilst “negotiating the linkage to the wider web”.

- Anna Mladentseva & Natalie Kane from the V&A spoke on the need for a care and community-informed preservation practice when handling complex media objects such as apps. Recognising that the infrastructures and knowledge required to care such objects often go beyond the museum, who are the communities we should be communing with in order to preserve digital object’s ‘edges’ (source code, emulation developers, groups writing the technical standards)?

- James Baker’s contribution to the Plenary positioned data environmentalism as a central concern for born-digital preservation. Current data collection and storage infrastructure cannot sustain the ever-expanding volume of born-digital content requiring preservation, particularly as generative AI accelerates this growth. Baker’s Digital Humanities Climate Coalition manifesto urges the archival community to confront the environmental consequences of the tech sector’s immense, monopolistic power. In the interest of informed choices, the coalition also offers practical tools for archives to measure and model their climate impact.

Lots to ponder on as we near the release of our Data Lifeboat and think deeper about our digital photo legacies. I’ll leave you, dear reader, with the following rumination:

Even if we were to save all the documents in the world, we still couldn’t save anyone’s spirit – Dorothy Berry