This blog post discusses the value of social media photography in enhancing our understanding and emotional vocabulary around historic events. It makes the case for a Data Lifeboat as a effective collecting tool for these types of citizen-made galleries (and histories). Additionally it also recounts the recommendation of other Data Lifeboat themes as collated during the Mellon co-design workshops.

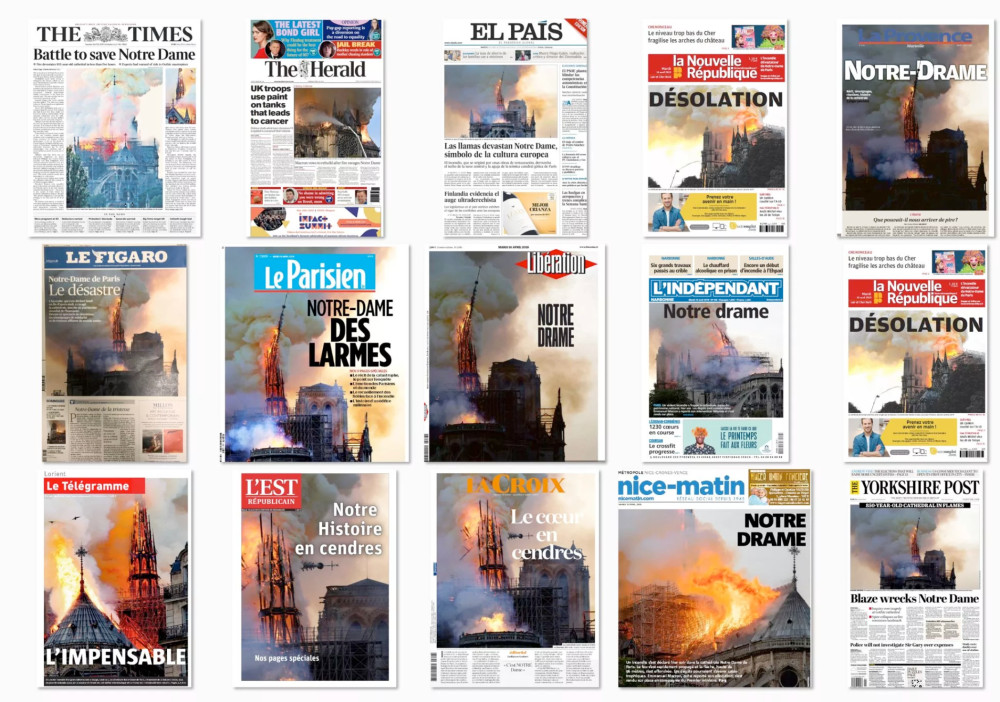

On Saturday, December 7th 2024, Notre Dame Cathedral reopened its iron-clad tracery doors, marking the end of a four-year closure. The news coverage focused on the splendour — and occasional controversy — of its distinguished guests, contentious seating plans and retro light shows. The reopening inevitably brought back memories of the 2019 tragedy that befell the cathedral, destroyed by fire. Somehow the event underscored our collective helplessness under the Covid-19 lockdowns as viewers could only watch in horror as the same images spread around news and social media. On reflection the ubiquity and uniformity of the images is surprising, so often captured from the southeast end of the chancel: the flechè engulfed in flames like a tapered candle, and behind it through the iridescent smoke, a pair of lancet windows seemed to peer back at the viewer, embodying a vision of Notre Dame des Larmes—Our Lady in tears.

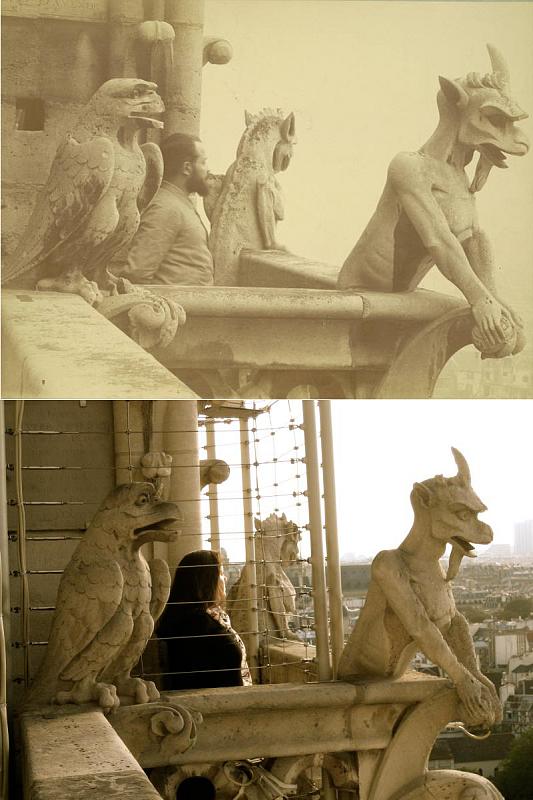

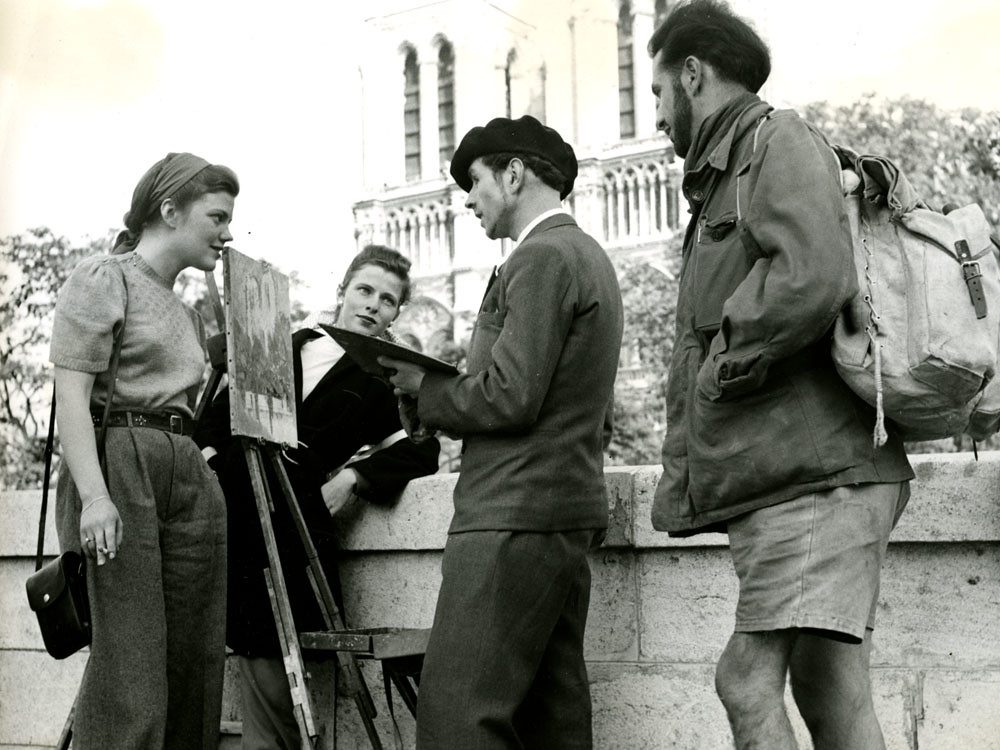

There is an alternative history of the Notre Dame fire, captured not through mainstream media but in the dispersed archives of networked social photography—an often overlooked and underreported lens on the event. Among the pictures gathered by the Flickr Foundation is a remarkable collection of street photographs that offer a fresh perspective (also shared in this post). These images place the fire in context: smoke billows against the backdrop of the Eiffel Tower as seen from Trocadéro; a woman in a fur coat strolls nonchalantly past the boarded-up bouquinistes; a couple steal a glance from their moped; a man abandons his bicycle, supplicating on the banks of the Seine. User-generated social photography expands the event from its mass-reproduced, singular, fixed perspective, into a multi-dimensional, multi-vocal narrative, that unfolds longitudinally over time.

This is the incantation of social photography at its best, so often dismissed for its sheer volume, producing images that are “unoriginal, obvious, boring.” Yet, as art historian Geoffrey Batchen counters, “There are no such things as banal photographs, only banal accounts of photography.” The true value lies not just in the images themselves, but in how we look at them. It is through this act of curation, contextualisation and interpretation that these photographs gain their depth.

A People’s History through the Lens

Embedded within the story of photography itself is a people’s history. From its inception, photography has centred the social subject, capturing the overlooked and hidden realities that traditional media refused to. In mid-19th century Paris, early photographers, Eugène Atget and Félix Nadar chronicled the changing urban landscapes, preserving scenes of working-class neighbourhoods, subject to Haussman’s destruction, proletarian characters and everyday life. The camera’s portability, speed and (perceived) candidness made it suitable to the task of documenting the unseen.

The social subject in photography has long been intended to elicit sentiment and action. Social photographs compel viewers to respond emotionally and, ideally, to take action. Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives (1888), aimed at middle-class audiences, used images of New York’s Lower East Side slums to generate empathy and drive charity. As Walter Benjamin later described it, the medium of photography has a “revolutionary use-value” in its ability to render visible hidden social structures. Contemporary documentary collections, such Kris Graves’s A Bleak Reality, have harnessed this historic compulsion to catalyse social change.

There is rightly so, caution against social photography’s treatment of its subjects. As Maren Stange argues, in her analysis of American documentary photographers including Riis (along with Hine and the famed Farm Security Administration collection), social photography has historically rested on assumptions about its subjects, instrumentalising them or reducing them to symbolic devices. Moreover, it often fails to acknowledge that the photographer inherently constructs the photograph’s reality. As David Peeler notes, each photograph holds “layers of accreted meanings” shaped by the photographer’s choice in composition, processing, and presentation. In the age of citizen-driven photography, with the distributed ability to manipulate images, these limitations become even more pronounced, requiring an explicit recognition of the constructed nature of the medium.

The construction of this fragment of reality in photography, however, is not inherently negative. When acknowledged, it can be a source of power, offering what Donna Haraway describes as situated knowledge—a rejection of objectivity in favor of partial, contextual perspectives. Citizen-driven collections, though subjective and, by their very nature incomplete, serve as an antidote to what Haraway calls the “conquering gaze from nowhere.” They counter dominant, institutional narratives with fragmented, personal views.

The Photograph Over Time

The value of a photograph often increases over time, as its meaning and significance evolve in relation to historical, cultural, and social contexts. Photographs gain depth through longitudinal perspectives, becoming more compelling at a distance as they reveal shifts, absences, and forgotten details. As Silke Helmerdig, in Fragments, Futures, Absence and the Past, discusses in her treatment of German photography of the 2010s, we ought to see photography as speaking to us in the future subjunctive, it asks us, “what could be, if?”

With time and attention, photographs can be viewed in aggregate, the future historian can pull from concurrent sources. Our contemporary photographic collecting tools, as in the case of Flickr’s Galleries and Albums, which allow curation of others people’s photographs, can come to resemble a sort of photomontage. Rosalind Krauss, writing on the photomontages of Hannah Höch and other Dadaists in The Optical Unconscious, argues that the medium forces a dialogue between images, creating unexpected connections and breaking the linearity of traditional visual narratives thus opening space for political critique. The Notre Dame gallery disrupts the throughline of the ‘official’ imagery of the event, creating a space for discourse of other elements besides the central action (e.g. gender, capitalism, urbanism).

Securing the People’s Archive

Having discussed the value of the citizen-made collection, this compels us to ask what if our institutional archives began collecting contemporaneously more? We believe Data Lifeboat can help with this. The Notre Dame Gallery is just one example of a potential collection for a Data Lifeboat: our tool for long-term preservation of networked social photography and citizen-made collections from Flickr.com.

Data Lifeboats could be deployed as a curatorial tool for networked social photography, providing institutions with a way to collect, catalogue and reflect on citizen-driven narratives. At present, there is not an archival standard for images on social media and archivists still struggle with the vastness and maintenance of those they’ve managed to collect [see our blog-post from iPres]. Data Lifeboat thus operates as a sort of packaging tool, flexible and light enough to adapt to collections of differing scales and purviews, but still maintaining the social context that makes networked images so valuable.

There are two potential approaches:

- Hands-on: Data Lifeboats could be commissioned by an institution around a certain topic. For example, the Museum of London could commission a group of Whitechapel teenagers to collect photos from Flickr.com of their neighbourhood spaces that are meaningful to them.

- Hands-off: Citizens create Data Lifeboats independently of a topic of their choosing. Institutions may choose to hold these bounded social media archives as a public good, for the benefit of our collective digital heritage.

In both cases, the institutions become holders of Data Lifeboats and they are subsumed into their digital collections management systems. Data Lifeboats become part of a process of Participatory Appraisal, extending and diversifying the ‘official archive’, addressing the persistent gap of who gets to be represented. As we have also discussed, there are also possibilities for distributing the load of Data Lifeboats, more on this in the Safe Harbor Network.

Other possible Data Lifeboats

During our Mellon-funded workshops, we asked participants to suggest Data Lifeboats they would like to see in their institutional collections, but also any they would create themselves for personal use.

At-risk Subjects

Collections focus on documenting vulnerable or ephemeral content that might disappear without active intervention. This includes both environmental changes and socio-political documentation that could be censored or lost.

e.g. glaciers over time, rapid response after a disaster, disappearing rural life across Europe, politically at-risk accounts

Subjects often overlooked

Collections that aim to preserve marginalised voices and underrepresented perspectives, helping to fill gaps in traditional institutional archives and ensure a more representative historical record.

e.g. a queer community coffee shop, Black astronauts, local street art, life in Communist Poland

Nostalgia for Web 1.0

As so much of Web 1.0 disappears (e.g. Geocities, MySpace music, see also ‘Digital Dark Age‘), there is a desire to archive and begin critically reflecting on the early days of the web.

e.g. self-portraits from the early 2000s, vernacular photography from the 2010s, Flickr HQ, most viewed Flickr photos

Quirky Collections

Flickr is renowned as a home for serendipitous discovery on the web, sometimes lauded as ‘digital shoebox of photographs’, there is the opportunity to replicate this ‘quirkiness’ with Data Lifeboats.

e.g. ghost signs, every Po’Boy in town, electricity pylons of the world

Personal collections

e.g. family archives, 365 challenges, a group of friends

Data Lifeboats could serve as secure containers for digital family heirlooms. Built into Flickr.com are privacy controls (Friends, Family) that would carry over to Data Lifeboats, preserving privacy for the long-term

Conclusion

The Notre Dame gallery exemplifies an ideal subject for a Data Lifeboat, both in its content and curatorial approach. The Data Lifeboat framework serves as an apt vessel, with its built-in capabilities:

- Data Lifeboats can capture alternative viewpoints, situated knowledges and stories from below through tapping into the vast Flickr archive. We recognise that we can never capture, nor preserve, the archive in its entirety, so Data Lifeboats tap into the logic of the archival sliver.

- Data Lifeboats can preserve citizen-driven communication through their unique storage of social metadata. This means that the conversations around the images are preserved with the images themselves, creating a holistic entity.

- Data Lifeboats are purposely designed with posterity in mind. Technologically, their light-touch design means they are built to last. Furthermore, the README (link) nudges the Data Lifeboat creator toward conscious curation and commentary, providing value to future historians.

Can you think of any other Data Lifeboats? We’d love to hear about them.