At the Flickr Foundation, you may have heard we’re developing a Digital Daybook—just one tangible codification of our 100-year plan. Answering the question, How might we keep Flickr alive for the next century?, is no easy feat, so we figured we might need some tools along the way to help us out.

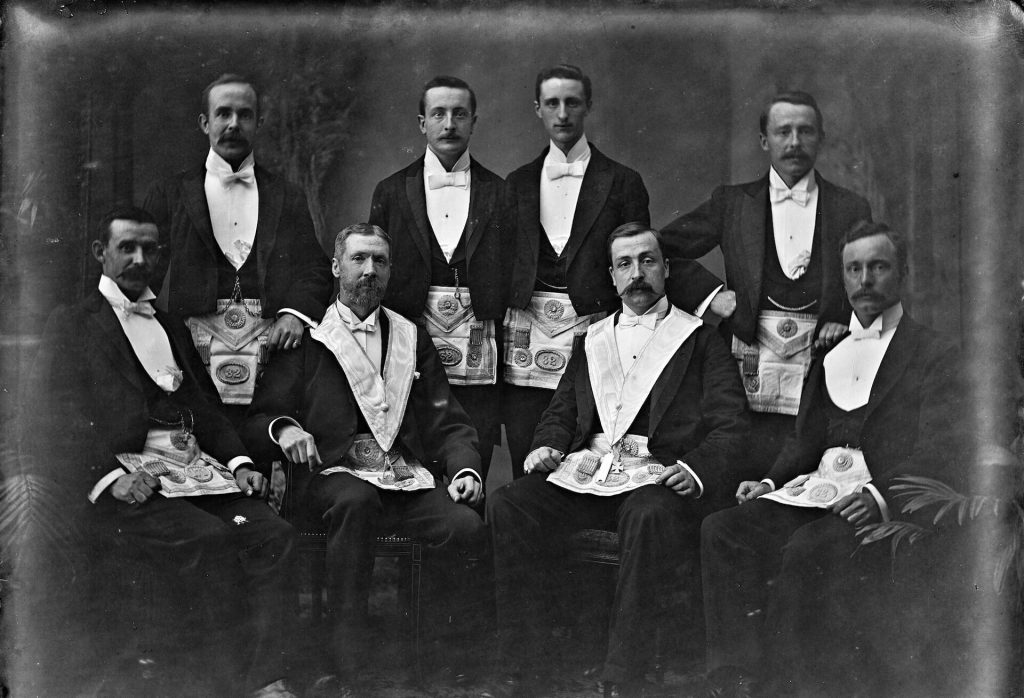

Through our 100-year plan workshops, one theme emerged again and again: it’s not just technical infrastructure that sustains an organisation, but social infrastructure, too. Shared rituals—the everyday and periodic habits, customs, and practices of a group—are just as critical to long-term preservation as robust servers and secure storage. Rituals create a sense of continuity and belonging, allowing knowledge, values, and ways of working to be carried forward even as individuals move on.

Rituals that Sustain

Take, for example, the Royal Society, founded in 1660. Today, it still upholds its core principles through rituals: formal presentations, roll calls, elections, and the meticulous recording of experiments and discussions in its journal, Philosophical Transactions. While the people, research priorities, and conditions for entry have changed, these rituals reinforce continuity and collective memory, ensuring that the institution’s intellectual traditions endure.

On the more speculative side, consider the Atomic Priesthood, a speculative proposal by a linguist (Thomas Sebeok), physicist (Alvin Weinberg) and science fiction writer (Arsen Darney) in the 1980s. They imagined a ritualistic system of knowledge transmission designed to warn future civilizations about nuclear waste disposal sites—long after current languages and cultural systems might have vanished. The idea was to establish a priesthood-like order that would embed knowledge of radioactive dangers into myths, superstitions, and religious customs, ensuring the information’s survival for millennia. The half-life of nuclear waste far exceeds a human lifespan, but rituals can endure — with the founders citing the Catholic Church’s survival over two millennia as proof of concept.

The kernel of history in the everyday

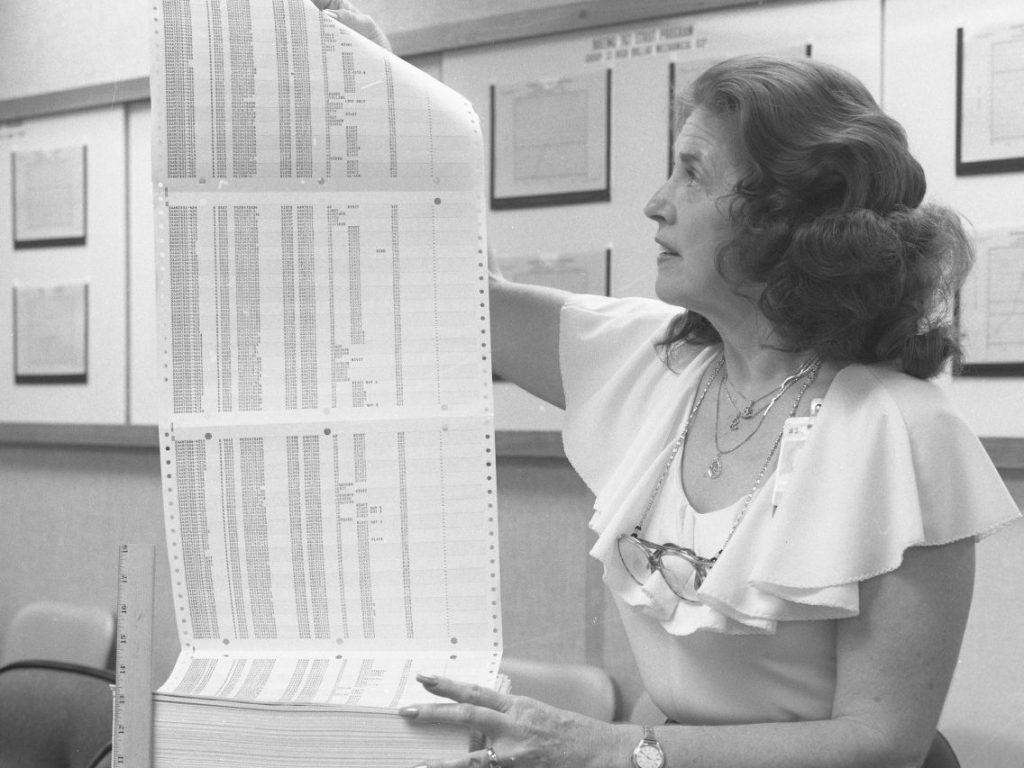

Beyond these grand and speculative examples of organisational sustenance, much of what we understand about historical institutions, corporations, and communities comes from the small, seemingly mundane records they leave behind. The minutiae of daily life—ledgers, journals, memos, meeting minutes, logbooks, annotations, schedules, receipts, rosters—constitute a form of ritual in themselves. These documents often appear purely practical in their own time, yet they later serve as a rich resource for historians.

Take, for example, a 19th-century household daybook discovered in Jönköping, Sweden. At first glance, it might seem like a simple log of purchases—how much sugar was bought, how much the gardener was paid. But when read with an attunement to the social, it reveals something more: the purchase of a bicycle for an 11-year-old girl, a quiet but profound marker of shifting ideas around childhood and womanhood in the fin-de-siècle.

Building the Foundation’s first ritual

As Flickr Foundation founder, George Oates, noted back in 2014, there’s an opportunity to view corporate corporate digital archives not as static documents, but “through a feeling of human activity and depth”—records imbued with the lived experience of the people who create them and the values of their time. Given our work at the Foundation, which so often deals with the care and consequences of archival materials, it only makes sense that we consider our own.

But the Digital Daybook isn’t just a gift to posterity. It’s also a tool for reflection in the present—a moment in our daily work routines to bring awareness to our own practices, values, and rhythms as we shape Flickr.org’s future.

In this series of blog posts, we’ll be crafting a sort of ‘prehistory’ to our own Digital Daybook, tracing its conceptual lineage and exploring its potential significance. First, we’ll ask: Where do daybooks appear? How have they functioned across history? Venturing into more unexpected corners, we’ll also survey adjacent ephemera that might be considered the spiritual ‘cousins’ of daybooks. In the subsequent post, we’ll examine what these records can reveal to us—about institutions, communities, and memory. Finally, we’ll turn to the role of the daybook in the digital era and what it means to document daily organisational life in an age of shifting technologies.